- Psychology 2.0

Arts and the communication of Cognitive Schemata

Psy2.Arts History

Show minor edits - Show changes to markup

(:include ad:)

(:include ad:)

(:include ad:)

Download in high quality (116 MB - 5:28)

(:keywords psychology, self, paradigm, communication, environment, altruism, aggression, sex, enlightenment, happiness, problem solving, religion, Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, relationship, couple, model, cognitive schemata, cognitive :)

(:description AESTHETICS / ART PSYCHOLOGY • FASHION • HORROR / PORNOGRAPHY • ILLUSTRATION • TEACHER • THEATER Communicating cognitive schemata through art. * Comparing FIPP and Berlyne's inverted U-shaped model. * Cultural embedding. * Differences between kitsch, art and "art". * Detective thrillers, thrilling horrors and horrid horrors. * The artist as a communicator. * What are fashions, and examples of good teachers, speakers, and illustration? * Beauty defined. :)

(:youtube X3gEDflC14E:)

In brief, that connection is of a certain parameter – for example, complexity, the number of colours, or density – that elicits an increasing pleasure. Measuring this from zero, that pleasure seems to reach an optimal, positive point, after which it begins to have a negative effect, which can then become disturbing to the observer of the artwork.

In brief, that connection is of a certain parameter – for example, complexity, the number of colors, or density – that elicits an increasing pleasure. Measuring this from zero, that pleasure seems to reach an optimal, positive point, after which it begins to have a negative effect, which can then become disturbing to the observer of the artwork.

Using FIPP as a generalised Berlyne model we can understand the difference between kitsch and art. The principal question with high art is that it is more difficult to understand. In contrast, as kitsch or popular art do not need intellectual effort to take them in, we realise that our efforts with higher art obtain a benefit. We can see that solving the mystery in an artwork – for example, where is the apple in the “scribble”? – is not an effort to see l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake), but enriches us by establishing new cognitive schemata. If we see a half-eaten apple after viewing Picasso’s apple, we might perceive new associations with it. Whereas with kitsch we need make no serious effort, and thus do not create cognitive schemata that can be used otherwise than in viewing a specific item of kitsch. So, kitsch does not enrich our knowledge or personalities.

Using FIPP as a generalized Berlyne model we can understand the difference between kitsch and art. The principal question with high art is that it is more difficult to understand. In contrast, as kitsch or popular art do not need intellectual effort to take them in, we realize that our efforts with higher art obtain a benefit. We can see that solving the mystery in an artwork – for example, where is the apple in the “scribble”? – is not an effort to see l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake), but enriches us by establishing new cognitive schemata. If we see a half-eaten apple after viewing Picasso’s apple, we might perceive new associations with it. Whereas with kitsch we need make no serious effort, and thus do not create cognitive schemata that can be used otherwise than in viewing a specific item of kitsch. So, kitsch does not enrich our knowledge or personalities.

To date, most of our knowledge is a hypothesis on a particular genre satisfying particular demands. This has resulted in a process whereby we classify genres considering the general human or ethical value (sex, eating, physical needs on the lowest levels; altruism, social work, self-realisation on the highest level; compare with the Maslow pyramid) of the demand they satisfy. Pornography and horror could be on the lowest level, followed by detective fiction, and on up to high art. But even critics admit that true genius can place superior messages – those which are of more use in one’s life than simple, targeted messages – in some of the genres classified as inferior. Edgar Alan Poe's detective stories provide such an example.

To date, most of our knowledge is a hypothesis on a particular genre satisfying particular demands. This has resulted in a process whereby we classify genres considering the general human or ethical value (sex, eating, physical needs on the lowest levels; altruism, social work, self-realization on the highest level; compare with the Maslow pyramid) of the demand they satisfy. Pornography and horror could be on the lowest level, followed by detective fiction, and on up to high art. But even critics admit that true genius can place superior messages – those which are of more use in one’s life than simple, targeted messages – in some of the genres classified as inferior. Edgar Alan Poe's detective stories provide such an example.

The contradiction can be released if we take into account that a new cognitive schema is created. We realise that sometimes we have to lose something to achieve higher goals. Naturally, we are happier when we win without effort or loss. But that is hardly the usual case.

The contradiction can be released if we take into account that a new cognitive schema is created. We realize that sometimes we have to lose something to achieve higher goals. Naturally, we are happier when we win without effort or loss. But that is hardly the usual case.

To explain the value of horror films, I shall review the film “Pink Flamingos” , which remarkably uses the technique that I call anti-catharsis. This film is concerned with making disgust limitless. Presented in a rather naturalistic manner, it is rare that all of the audience can watch it through to the end. I do not consider myself inhibited, but I could only watch the first third. The film centres on two disgusting people competing to determine which of them can do something more disgusting than the other.

To explain the value of horror films, I shall review the film “Pink Flamingos” , which remarkably uses the technique that I call anti-catharsis. This film is concerned with making disgust limitless. Presented in a rather naturalistic manner, it is rare that all of the audience can watch it through to the end. I do not consider myself inhibited, but I could only watch the first third. The film centers on two disgusting people competing to determine which of them can do something more disgusting than the other.

However, to return to horror. “Pink Flamingos” is an atypical horror film: it is not full of blood and gore, and one is not scared all of the time. But the mechanism is the same: after we are frightened, our Self narrows intensely, we switch off the TV and, when we realise that we are in our warm cosy room, slip into a soft bed and, unless we dream about the film, we can then become Self-expanded.

However, to return to horror. “Pink Flamingos” is an atypical horror film: it is not full of blood and gore, and one is not scared all of the time. But the mechanism is the same: after we are frightened, our Self narrows intensely, we switch off the TV and, when we realize that we are in our warm cosy room, slip into a soft bed and, unless we dream about the film, we can then become Self-expanded.

An example of this is Shakespeare. In his time the theatre was visited by people of all classes and rank. Shakespeare was able to satisfy that range of interests and demands in the same play. For instance, Hamlet loved Ophelia (romantic feelings for ladies), it has many duels (aggression for men), but one’s own schema can be enriched with further topics: family affairs, jealousy, politics &c.

As for pornography…the value of the film “Emmanuelle” is that, apart from the spectacle of naked bodies and sexual intercourse, it attempts to explain the power of feminine beauty and the different roles a woman can have.

An example of this is Shakespeare. In his time the theater was visited by people of all classes and rank. Shakespeare was able to satisfy that range of interests and demands in the same play. For instance, Hamlet loved Ophelia (romantic feelings for ladies), it has many duels (aggression for men), but one’s own schema can be enriched with further topics: family affairs, jealousy, politics &c.

As for pornography…the value of the film “Emanuele” is that, apart from the spectacle of naked bodies and sexual intercourse, it attempts to explain the power of feminine beauty and the different roles a woman can have.

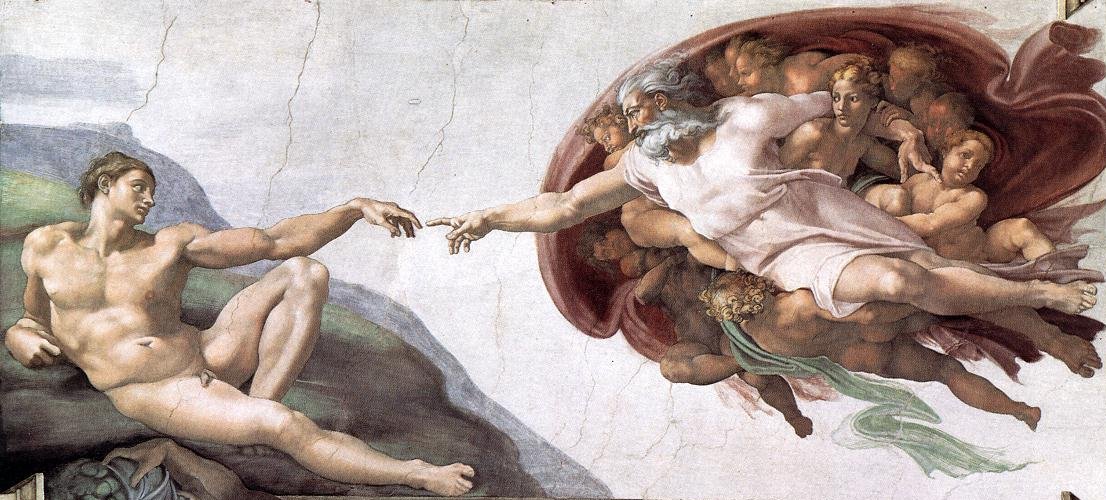

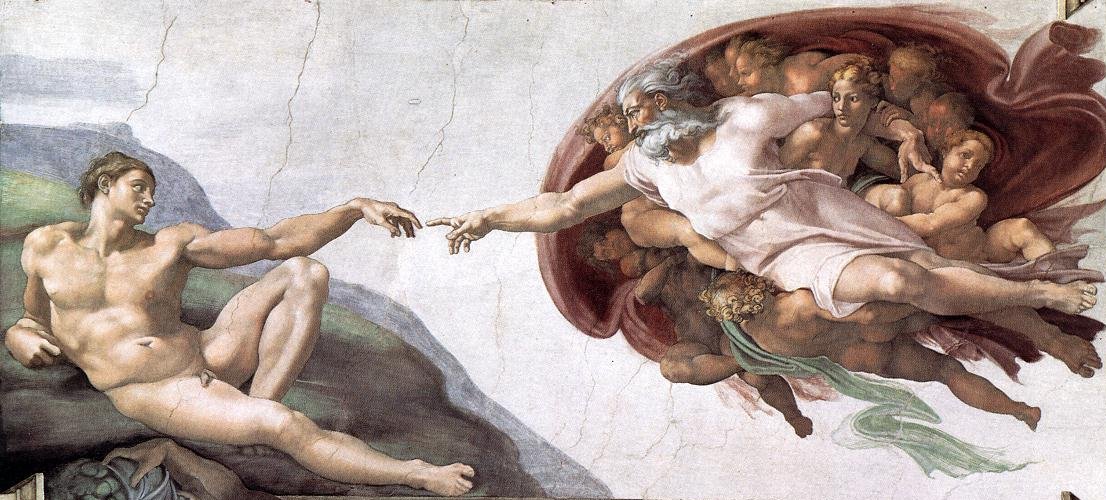

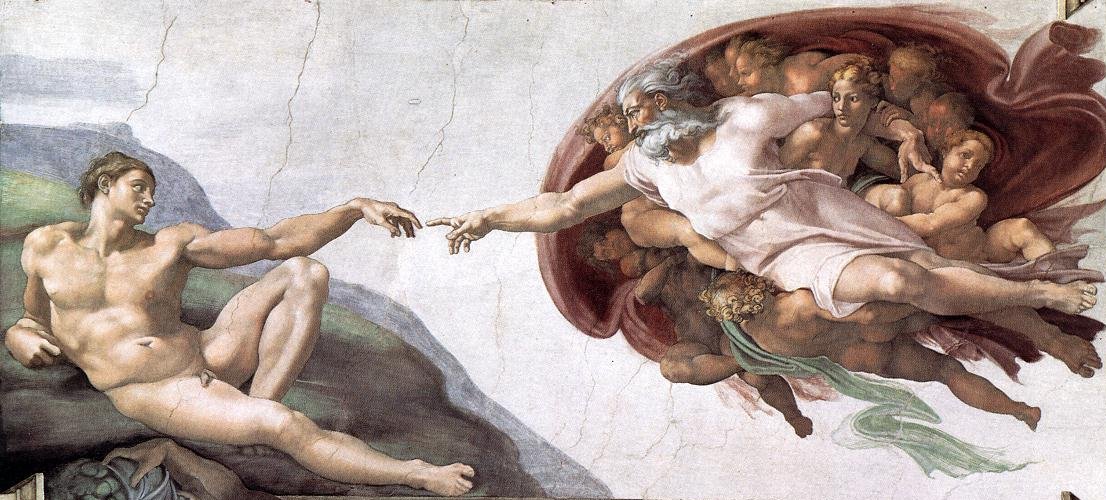

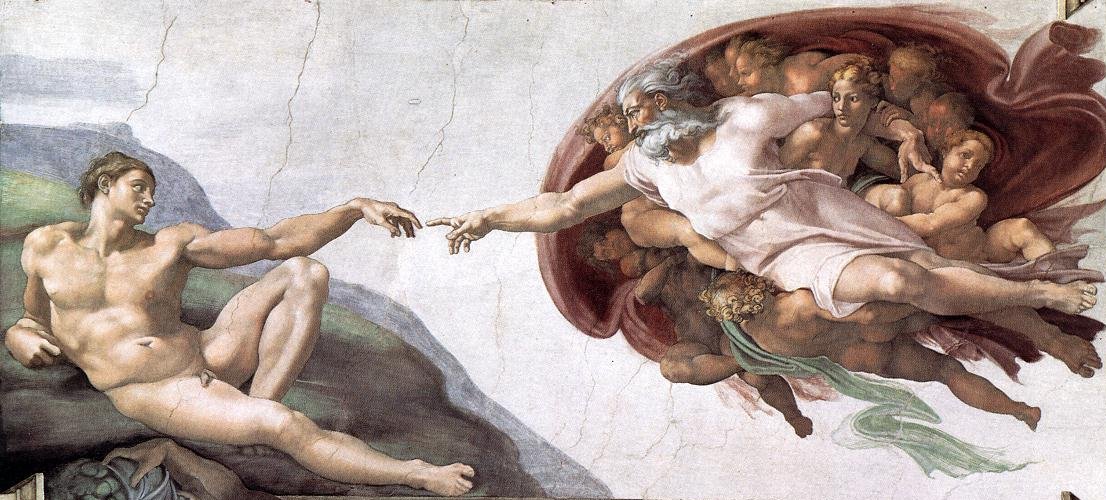

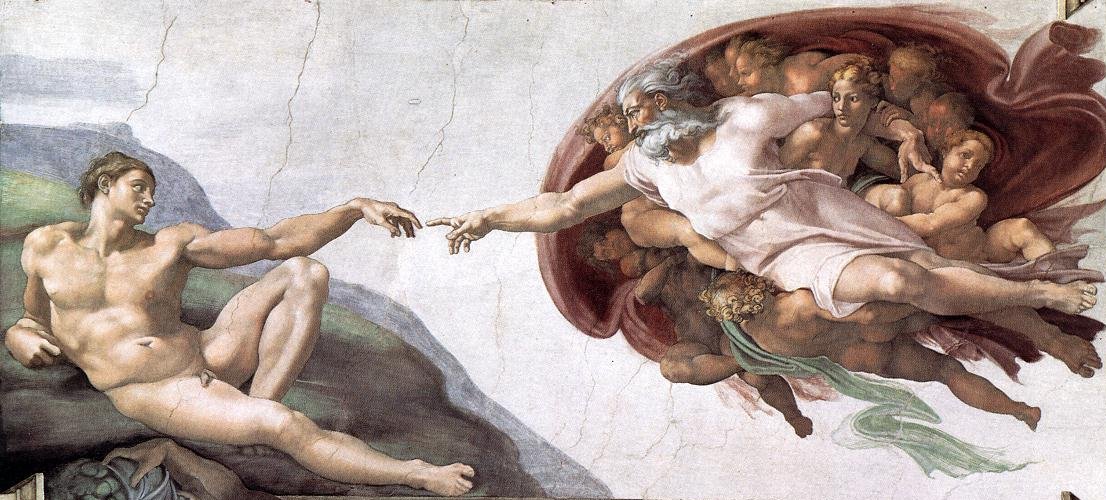

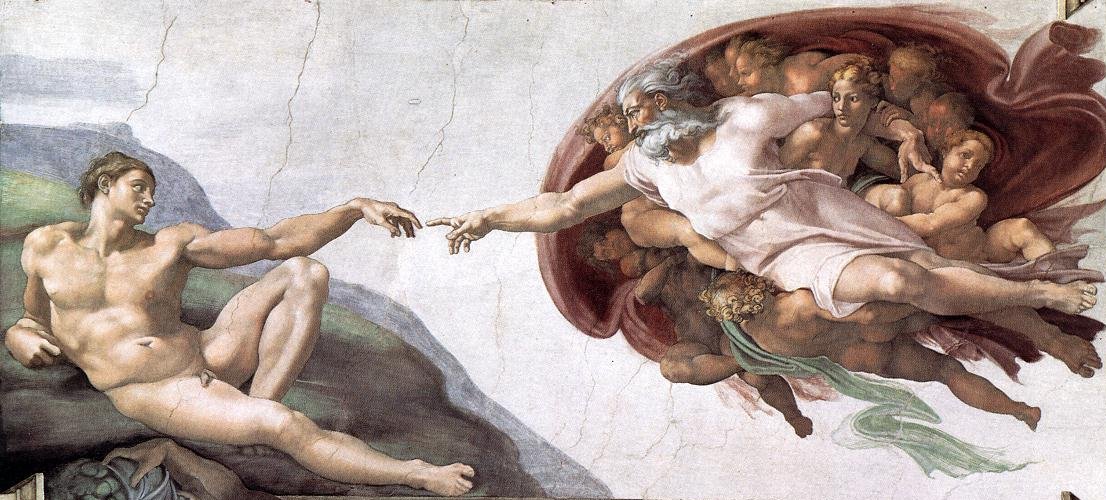

In the process of artistic creation (=physical realisation), technical ability (knowing how to paint and how to convey your internal pictures onto a canvas) connect with the quality of communication. So, if he had not thought so much about it, the message obtained by observers would leave them with difficulties in interpreting and understanding the painting. Fortunately, in this instance we have a painting where not only the concept, but also its realisation, is exceptional. Note in particular the solution in the structure of the picture: the hand of God barely touches Adam, so accentuating the tension.

In the process of artistic creation (=physical realisation), technical ability (knowing how to paint and how to convey your internal pictures onto a canvas) connect with the quality of communication. So, if he had not thought so much about it, the message obtained by observers would leave them with difficulties in interpreting and understanding the painting. Fortunately, in this instance we have a painting where not only the concept, but also its realization, is exceptional. Note in particular the solution in the structure of the picture: the hand of God barely touches Adam, so accentuating the tension.

- based on the new cognitive schema new, but lower level, schemata are created via deduction (e.g. in the beginning everybody thought that armless T-shirts in black were funny, then somebody tried armless T-shirts in colours)

- when the new cognitive schemata have become known by the majority of the population, and there are then no possibilities for further deduction, the clothes or behaviour based on this cognitive schema disappear and a new one appears and starts to spread (e.g. perhaps armless T-shirts with turtle-necks)

- based on the new cognitive schema new, but lower level, schemata are created via deduction (e.g. in the beginning everybody thought that armless T-shirts in black were funny, then somebody tried armless T-shirts in colors)

- when the new cognitive schemata have become known by the majority of the population, and there are then no possibilities for further deduction, the clothes or behavior based on this cognitive schema disappear and a new one appears and starts to spread (e.g. perhaps armless T-shirts with turtle-necks)

To discuss this topic, let us ignore a teacher’s personality, and that people prefer others who are similar to them or, in certain instances, diametrically different to them (Newcomb(1961): The aquaintance process. New York, Plt). The examination of the qualities of a good teacher or lecturer are more effective indicators.

To discuss this topic, let us ignore a teacher’s personality, and that people prefer others who are similar to them or, in certain instances, diametrically different to them (Newcomb(1961): The acquaintance process. New York, Plt). The examination of the qualities of a good teacher or lecturer are more effective indicators.

In the mid 1980s I learnt that, if a director wants to avoid a film becoming boring and losing the audience’s interest in watching it, then every seven minutes something new must happen; a turn, exciting action, a new riddle, a new solution &c.

In the mid 1980s I learned that, if a director wants to avoid a film becoming boring and losing the audience’s interest in watching it, then every seven minutes something new must happen; a turn, exciting action, a new riddle, a new solution &c.

To sum up, a good dramatic advisor, together with a good director and cameraman (those who guarantee the technical realization, providing the craftsmanship mentioned in the Michelangelo example) can play with the size of our Selves in a manner that is good for us.

A good wooer does the same with girls' self and their self-confidence when he varies compliments and affects either complete attention or indifference and neglectful behaviour. These variances force the other party to be fully engaged and so they turn toward the wooer with greater attention; the chosen person’s Environment is filled with the tactical wooer. She fears that she will miss messages that could increase her confidence and therefore she might remain completely ignored.

To sum up, a good dramatic adviser, together with a good director and cameraman (those who guarantee the technical realization, providing the craftsmanship mentioned in the Michelangelo example) can play with the size of our Selves in a manner that is good for us.

A good wooer does the same with girls' self and their self-confidence when he varies compliments and affects either complete attention or indifference and neglectful behavior. These variances force the other party to be fully engaged and so they turn toward the wooer with greater attention; the chosen person’s Environment is filled with the tactical wooer. She fears that she will miss messages that could increase her confidence and therefore she might remain completely ignored.

- it is easy to overview it. It should display only one or two thoughts. In other words we can say that it is focussed

- it is easy to overview it. It should display only one or two thoughts. In other words we can say that it is focused

Similarly, it is also important to determine which cognitive schemata are active and accessible when a person is looking at a piece of art. That is why the surroundings are so important. (For example, when looking at a painting, is the museum quiet, silent, is the lighting good, what are the frames like, are the colour of the walls apprpriate to the hanging, is the building sympathetic to the piece.) All of these circumstances have a priming effect. In psychology, priming means that the former perception of certain stimuli predisposes us to certain answers and mental states in an ensuing situation.

Similarly, it is also important to determine which cognitive schemata are active and accessible when a person is looking at a piece of art. That is why the surroundings are so important. (For example, when looking at a painting, is the museum quiet, silent, is the lighting good, what are the frames like, are the color of the walls appropriate to the hanging, is the building sympathetic to the piece.) All of these circumstances have a priming effect. In psychology, priming means that the former perception of certain stimuli predisposes us to certain answers and mental states in an ensuing situation.

- The formalised description of:

- The formalized description of:

Cataharsis

Catharsis

bla-bla

bla-bla

(:drawing tempo:)

(:drawing tempo:)

(:drawing lecturer:)

(:drawing lecturer:)

(:drawing tempo:)

(:drawing tempo:)

(:drawing lecturer:)

(:drawing lecturer:)

A good visual example on priming is of two persons' profile, which from another point of view might be seen as a vase (that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see a profile). Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece.

A good visual example on priming is of two persons' profile, which from another point of view might be seen as a vase (that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see two profiles). Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece.

http://www.psy2.org/images/vase.jpg%%

The function of presentation is to help the communicational process by opening a visual channel above the auditory channel to the audience. As we know from the principles of Psychology 2.0, a good figure or diagram helps more the understanding than 10 pages of written material.

The function of presentation is to help the communicational process by opening a visual channel above the auditory channel to the audience. As we know from the principles of Psychology 2.0, a good figure or diagram helps more the understanding than 10 pages of written material.

The function of presentation is to help the communicational process by opening a visual channel above the auditory channel to the audience. As we know from the principles of Psychology 2.0, a good figure or diagram helps more the understanding than 10 pages of written material.

The function of presentation is to help the communicational process by opening a visual channel above the auditory channel to the audience. As we know from the principles of Psychology 2.0, a good figure or diagram helps more the understanding than 10 pages of written material.

Why is an article related to art psychology the first example mentioned in Fodormik's Integrated Paradigm for Psychology (FIPP)? Because the whole model is rooted in art psychology.

Why is an article related to art psychology the first example mentioned in Fodormik's Integrated Paradigm for Psychology (FIPP)? Because the whole model is rooted in art psychology.

Profit from present article:

Principal points covered in this article:

(:include fipp.short:)

(:include short:)

- The formalised description of: kitsch-art difference;

- The formalised description of:

- kitsch-art difference;

(:include MPP.short:)

(:include fipp.short:)

To explain the value of horror films, I shall review the film “Pink Flamingos” , which remarkably uses the technique that I call anti-catharsis. This film is concerned with making disgust limitless. Presented in a rather naturalistic manner, it is rare that all of the audience can watch it through to the end. I do not consider myself inhibited, but I could only watch the first third. The film centres on two disgusting people competing to determine which of them can do something more disgusting than the other.

To explain the value of horror films, I shall review the film “Pink Flamingos” , which remarkably uses the technique that I call anti-catharsis. This film is concerned with making disgust limitless. Presented in a rather naturalistic manner, it is rare that all of the audience can watch it through to the end. I do not consider myself inhibited, but I could only watch the first third. The film centres on two disgusting people competing to determine which of them can do something more disgusting than the other.

To explain the value of horror films, I shall review the film “Pink Flamingos” , which remarkably uses the technique that I call anti-catharsis. This film is concerned with making disgust limitless. Presented in a rather naturalistic manner, it is rare that all of the audience can watch it through to the end. I do not consider myself inhibited, but I could only watch the first third. The film centres on two disgusting people competing to determine which of them can do something more disgusting than the other.

To explain the value of horror films, I shall review the film “Pink Flamingos” , which remarkably uses the technique that I call anti-catharsis. This film is concerned with making disgust limitless. Presented in a rather naturalistic manner, it is rare that all of the audience can watch it through to the end. I do not consider myself inhibited, but I could only watch the first third. The film centres on two disgusting people competing to determine which of them can do something more disgusting than the other.

A good visual example is of a person’s profile, which from another point of view may be a vase; that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see a profile. Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece. To summarize, we can say that beauty is nothing but a cognitive schema – object, event, phenomenon, person, thought – which can be incorporated amongst our existing cognitive schemata, can totally connect with them and, as it is new, so elicit Self-expanding. The more cognitive schemata it can connect to, and the better its connection, the greater our perception of its beauty.

A good visual example on priming is of two persons' profile, which from another point of view might be seen as a vase (that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see a profile). Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece.

To summarize, we can say that beauty is nothing but a cognitive schema – object, event, phenomenon, person, thought – which can be incorporated amongst our existing cognitive schemata, can totally connect with them and, as it is new, so elicits Self-Expansion. The more cognitive schemata it can connect to, and the better its connection, the greater our perception of its beauty.

The formalised description of: kitsch-art difference; commercial and high art; the mechanism of artistic pleasure; mechanism of beauty's independence from genres; and MPP can also form the basis of a new aesthetics

- The formalised description of: kitsch-art difference;

- commercial and high art;

- the mechanism of artistic pleasure;

- mechanism of beauty's independence from genres;

- FIPP can also form the basis of a new aesthetics

Similarly, it is also important to determine which cognitive schemata are active and accessible when a person is looking at a piece of art. That is why the surroundings are so important. (For example, when looking at a painting, is the museum quiet, silent, is the lighting good, what are the frames like, are the colour of the walls apprpriate to the hanging, is the building sympathetic to the piece.) All of these circumstances have a priming effect. In psychology, priming means that the former perception of certain stimuli predisposes us to certain answers and mental states in an ensuing situation. A good visual example is of a person’s profile, which from another point of view may be a vase (:drawing vase:); that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see a profile. Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece.

Similarly, it is also important to determine which cognitive schemata are active and accessible when a person is looking at a piece of art. That is why the surroundings are so important. (For example, when looking at a painting, is the museum quiet, silent, is the lighting good, what are the frames like, are the colour of the walls apprpriate to the hanging, is the building sympathetic to the piece.) All of these circumstances have a priming effect. In psychology, priming means that the former perception of certain stimuli predisposes us to certain answers and mental states in an ensuing situation.

A good visual example is of a person’s profile, which from another point of view may be a vase; that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see a profile. Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece.

People call different things nice, and that is what makes defining beauty difficult. We can use the word "beautiful" perfectly, we only have problems with its definition. Maybe Kant defined it the best when he said: ”In general beauty is what we like without interest.” (Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft, hrsg. von H.F. Klemme. Mit Sachanmerkungen von P. Giordanetti, Meiner, Hamburg, 2001 (2006) ). MPP has an explanation for this phenomenon and also suggests a definition for beauty.

Let us start understanding why does not everybody like the same things and why they call different things nice. The answer lies in the difference of our cognitive schemata, and in the fact that even if we have the same cognitive schemata, they are connected differently. Take the example of the word "Madonna": a young ateist will associate the name with the musician, the catholic believer will associate it with the Blessed Virgin, and someone studying for the Italian language exam will associate it with the word Madame.

Similar to this it is also important which cognitive schemata are active and accessible when someone is looking at a work of art. That is why the surrounding is so important (for example when looking at a painting whether the museum is silent, the lighting is good, what are the frames like, whether the color of the walls are fitting, what is the building look like). These are all circumstances which have a priming effect. ((In psychology priming means that the former perception of certain stimuli predispose us to certain answers, and mental states in the following situation. A good visual example for that is the profiles, which is a vase from another point of view (ÁBRA). If we watch cups before the profiles then we will see a vase, and if we watch faces before it, then will see the profiles. Priming helps that an artwork should have an effect and if it has one it should be maximized. This is done by helping that the cognitive scheme should be incorporated within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the artwork.

To sum up we can say that beauty is not else but a cognitive scheme (object, event, phenomenon, person, thought) which can be perfectly incorporated among our existing cognitive schemata, can totally connect to them, and as it is new, it elicits Self-expanding. The more cognitive schemata it can connect to, and the better it connects, the more beautiful we perceive it.

Profit from present article:

The formalised description of: -kitsch-art difference -commercial and high art -the mechanism of artistic pleasure -beauty's mechanism's independency from genres

And MPP can be also the basis of a new aesthetics

Different things are “nice” to different people, so making the definition of beauty difficult. We can use the word "beautiful" although we may have problems with its definition. Maybe Kant best defined it when he said: “In general beauty is what we like without interest.” (Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft, hrsg. von H.F. Klemme. Mit Sachanmerkungen von P. Giordanetti, Meiner, Hamburg, 2001 (2006) ). FIPP has an explanation for this phenomenon, and suggests a definition for beauty.

Let us begin by attempting to understand why everybody does not like the same things and why they call different things “nice”. The answer lies in the differences of our cognitive schemata Even if we had the same cognitive schemata, they are connected differently. For example, the word "Madonna": an atheist or agnostic will associate the name with the musician, a Catholic will associate it with the Blessed Virgin, and someone studying for an Italian language exam will associate it with the word Madame.

Similarly, it is also important to determine which cognitive schemata are active and accessible when a person is looking at a piece of art. That is why the surroundings are so important. (For example, when looking at a painting, is the museum quiet, silent, is the lighting good, what are the frames like, are the colour of the walls apprpriate to the hanging, is the building sympathetic to the piece.) All of these circumstances have a priming effect. In psychology, priming means that the former perception of certain stimuli predisposes us to certain answers and mental states in an ensuing situation. A good visual example is of a person’s profile, which from another point of view may be a vase (:drawing vase:); that may depend upon what we have seen immediately before, so that having viewed a cup we then see a vase, or having seen a portrait we then see a profile. Priming helps an artwork to have an effect, if that is one to be maximized. This is achieved by incorporating the cognitive schema within the same schemata that the artist had when he designed the piece. To summarize, we can say that beauty is nothing but a cognitive schema – object, event, phenomenon, person, thought – which can be incorporated amongst our existing cognitive schemata, can totally connect with them and, as it is new, so elicit Self-expanding. The more cognitive schemata it can connect to, and the better its connection, the greater our perception of its beauty. Profit from present article: The formalised description of: kitsch-art difference; commercial and high art; the mechanism of artistic pleasure; mechanism of beauty's independence from genres; and MPP can also form the basis of a new aesthetics

The lecturer must also have reasonable targets. The lecturer has a real chance to establish cognitive schemata within the audience only just one or two levels higher than their originally existing ones. (It is difficult to explain Maxwell-equations based on primary school knowledge.). New, but too low cognitive schemata do not elicit great Self-Expansion, although occasionally it is necessary to broaden our knowledge by learning listed items without any obvious structure (e.g. learning by heart the name of U.S. presidents or the name of states). Even then, (if possible or if exists) it is of greater interest if we first realize the common idea behind the list. There is a difference of learning a row of random numbers (e.g. phone directory) than learning the names of different muscles of the human body (anatomy). Although the latter one seems to be also random, the names have an internal logics and by learning them, the medicine student creates a cognitive scheme of the physical basics of the human body.

If the Self-narrowing phase is overlong, people may give up (either by physically leaving the classroom or by turning their attention away). The other setback is when the audience feels that the Self-expansion is not in balance with the former Self-narrowing. For example, when after a long explanation, the lecturer sheds light on a fact that is already known for almost everybody.

Occasionally, a lecturer is incapable of empathizing with the audience: their cognitive schemata are on such a different level that they cannot communicate. For example, where a professor of mathematics explains summation to a primary school pupil. Even if he can do that, it is not good for either of them: whenever a teacher explains and proves a thesis, he rebuilds the cognitive schema in himself and experiences a small Self-expansion, or perhaps realizes some new aspect and so obtain greater Self-expanding. However, in the case of very low cognitive schemata perhaps the most that the professor facing the primary school pupil can gain is the pleasure of imparting the methodology, the manner of his explanation, his examples etc.

Returning to the issue of personality: in the case of a practised lecturer choosing the proper level of cognitive schemata is mostly a conscious process. Thus, the selection of the target level may communicate also unconscious motives e.g. political views: those who impatiently with the less talented students demand of the audience that it attempt to leap several levels understands that only the most talented students will follow him, so indicating an elitist focus (those who were unable to follow him might never catch up with the topic). Those who take into consideration, and want to help the development of, the least clever ones – notwithstanding that that will affect negatively clever students – are likely to have a sympathy for socialist or social democrat philosophy in the everyday life. It is logical that the former requirement – of a leap of several levels -, will be favoured only by the elite, and that the latter will be favoured by the rest.

This position is the same when calling students to account, or for the form or quantity or both of their homework. We may even consider a personality trait: how much does the teacher prefer visual tools, or how visual does he or she think? Those students who have an auditory focus will dislike lecturers who always use charts and figures.

The good movie

I heard in the mid '80s that if a director wants to avoid that a movie becomes boring and the audience looses interest in wacthing it, then there has to happen something new in every 7 minutes: a turn, exciting action, a new riddle, or a new solution etc.

It is a fact that the intense attention is not endless in time: sooner or later it weakens and turns to something else. Movies which give us new and new stimuli within this attention weakening period we can call fast pacing movies (a great master of it is Tarantino, but maybe the best example is the series 24).

According to our theory, what happens in these fast pacing movies is that the director is changing the Self-narrowed and Self-expanded phases: the tension (Self-narrowing) and the solution (Self-expanding) changes rhythmically (or at least periodically), and also new story-lines, possibilities, new points of view (altogether new can view them as mini-paradigms or new mini frameworks) show up, which cause further Self-expanding. Raising new questions (the mini-paradigms) also require new (lower-level) cognitive schemata. The partial solutions for the partial problems give us small aha experiences, but previously they also unavoidably lead to Self-narrowing.

From this point of view, dramaturgy is the art of mixing these elements the optimal way, which can only be achieved by careful planning. Since, if the elements from different source and of different intensity are not distributed and placed well enough, then we become disorganised (we either become disturbed by the overflow of stimuli, or become bored because of the lack of sufficient stimuli).

(For example killing in an action film is a typical method for self-narrowing, but when a negative character is killed in a long fight in which the hero almost dies as well, that will lead to Self-expanding. The love scenes cause Self-expanding, partially through empathy (we enter into the spirit of the character – how good it must be for him: e.g. kissing, being teased etc.), and partially because generally love means the solution of a problem within the film, which anticipates the solution of the respective conflict.)

To sum up, a good dramatic advisor together with a good director and a good camera man (those who guarantee the technical realization for the acquired effectiveness c.p. craftsmanship mentioned at the example from Michelangelo) can play with the size of our Selves in a way which is good for us.

A good wooer does the same with girls' self and their self-confidence when he varies the compliment and complete attention with indifference and neglecting behaviour. This varying forces the other party to be fully on alert and turn toward the wooer with greater attention (so the chosen person’s Environment fills up with the tactical wooer), since it is to be feared that she misses messages that could increase her confidence and so she might remain in totally ignored position.

In both cases (film and courting) the key is not to let the people's Self rest, AND to make sure that the overall process will lead to a future Self-expantion. So the creators and the wooers have to meet expectations on two levels:

- inside the process, at different occasions there has to be several small Self-expandings and

- the whole process has to lead to Self-expading. For example the movie has something to tell, gives a new cognitive schema or a love comes true which is again a new cognitive schema (the cognitive scheme „Us” is formed instead of the cognitive schemata of „You” and „Me”).

The lecturer must also have reasonable targets. The lecturer has a chance to establish cognitive schemata within the audience only one or two levels higher than those they had before the lecture. (Note that it is difficult to explain Maxwell equations based on primary school knowledge.) New, but too low cognitive schemata, do not elicit great Self-Expansion, although occasionally it is necessary to broaden our knowledge by learning listed items without any obvious structure; for example, learning by rote the name of U.S. presidents or the names of the states). Even then, it is of greater interest if we first realize the common idea behind the list. There is a difference of learning a row of random numbers, perhaps those in a telephone directory, than by learning the names of different muscles of the human body (anatomy). Although the latter seems also to be random, the names have an internal logic. By learning them, a medicine student creates a cognitive schema of the physical basis of the human body.

If the Self-Narrowing phase is overlong, people may give up, by physically leaving the classroom or by turning their attention elsewhere. Another drawback is when the audience feels that the Self-Expansion is not in balance with the former Self-Narrowing. (For example, when after a long explanation, the lecturer sheds light on a fact that was previously known to almost everybody.)

Occasionally, a lecturer is incapable of empathizing with the audience: their cognitive schemata are on such a different level that they cannot communicate. For example, where a university professor of mathematics explains summation to a primary school pupil. Even if he can do that, it is not good for either of them: whenever a teacher explains and proves a thesis, he rebuilds the cognitive schema in himself and experiences a small Self-expansion, or perhaps realizes some new aspect and so obtains greater Self-expanding. However, in the case of very low cognitive schemata, perhaps the most that the professor facing the primary school pupil can gain is the pleasure of imparting the methodology, the manner of his explanation, his examples and so forth.

To return to the issue of personality: for a seasoned lecturer, choosing the proper level of cognitive schemata is mostly a conscious process. Thus, the selection of the target level may communicate also unconscious motives e.g. political views. So, those who deal impatiently with less talented students demand of the audience that it attempt to leap several levels while understanding that only the most talented students will follow him, so indicating an elitist focus; (those who were unable to follow him might never catch up with the topic). Those who take the less talented into consideration, and want to help their development – notwithstanding that that will affect negatively clever students – are likely to have sympathy with socialist or social democrat philosophy in everyday life. It is logical that the former requirement – of a leap of several levels – will be favoured only by the elite, and that the latter will be favoured by the rest.

This position is the same when calling students to account, or for the form or quantity, or both, of their homework. We may even consider a personality trait: how much does the teacher prefer visual tools, or how visual does he or she think? Those students who have an auditory focus will dislike lecturers who always use charts and figures.

The good film

In the mid 1980s I learnt that, if a director wants to avoid a film becoming boring and losing the audience’s interest in watching it, then every seven minutes something new must happen; a turn, exciting action, a new riddle, a new solution &c.

Intense attention cannot be endless in time. It will eventually weaken and turn to something else. Films which periodically give us new stimuli within this attention weakening period can be called fast-paced; a master this genre is Tarantino, or perhaps a better example is the television series “24”.

According to our theory, what happens in these fast-paced films is that the director changes the Self-narrowed and Self-expanded phases: the tension (Self-Narrowing) and the solution (Self-Expansion) change rhythmically (or at least periodically), and also new story-lines, possibilities, points of view… Anything new can be viewed as mini-paradigms or new mini frameworks, which cause further Self-expanding. Raising new questions (the mini-paradigms) also requires new (lower-level) cognitive schemata. The partial solutions for the partial problems give us small aha experiences, but previously they also unavoidably led to Self-narrowing.

From this point of view, dramatic advisory is the art of mixing these elements optimally, which can only be achieved by careful planning. As, if the elements from different sources and of different intensity are not distributed and placed well enough, then we become disorganized; we either become disturbed by the overflow of stimuli, or become bored because of the lack of sufficient stimuli.

(As an example, a murder in an action film is a typical method for self-narrowing, but when a negative character is killed in a long fight in which the hero almost dies as well, that will lead to Self-expanding. Love scenes cause Self-expanding, partially through empathy (we enter into the spirit of the character, how good it must be for him,kissing, being teased. Also, because, generally, love means the solution of a problem within the film, which anticipates the resolution of the respective conflict.)

To sum up, a good dramatic advisor, together with a good director and cameraman (those who guarantee the technical realization, providing the craftsmanship mentioned in the Michelangelo example) can play with the size of our Selves in a manner that is good for us.

A good wooer does the same with girls' self and their self-confidence when he varies compliments and affects either complete attention or indifference and neglectful behaviour. These variances force the other party to be fully engaged and so they turn toward the wooer with greater attention; the chosen person’s Environment is filled with the tactical wooer. She fears that she will miss messages that could increase her confidence and therefore she might remain completely ignored.

In both cases (film and courting) the key is not to let the Self of people rest AND to ensure that the overall process will lead to future Self-expansion. So, creators and wooers have to meet expectations on two levels:

- inside the process, on different occasions there have to be several small Self-expandings; and

- the whole process has to lead to Self-Expansion. For example, the film has something to tell, providing a new cognitive schema, or a love comes true which is again a new cognitive schema (the cognitive schema “Us” is formed instead of the cognitive schemata “You” and “Me”.

A good speech is based on similar principles, with the difference that in this case less visual, but far more intellectual tools can be used. According to the general set up, someone stands on the stage and talks. Probably he uses figures for the explanation.

The good speech has one (or more) clear main message for the audience. This message is an evidence (a new cognitive scheme) in most cases. The more distant the connected things are (for example if it tries to put something in a political, social, or historical context, which is not obviously expected) the bigger is the Self-expanding effect of the birth of the new scheme.

If the speech would have started with the point, then the message would be communicated, but it would lack understanding (of course sometimes we start with the point but then it is shockingly complex and un-understandable for the first time). It is a widespread method of the speaker to repeat the way how he reached the new evidence, similar as the Christian world does every year at Easter with the Passion of Christ (passion = the last hours of Jesus before he was crucified). The advantage of this method is that many sub-problem and the joy of their solutions can be communicated supposedly that this doesn’t happen in order to increase the ego of the speaker listing how heroic he fought with the problems. If the sub-problems are interesting as such, and if they mobilize the cognitive schemas which are around the cognitive schema to be introduced it might have a bigger effect. This solution makes possible that cognitive schemas should connect faster with the new evidence (cognitive-scheme) as they trigger the schemata around the future scheme and so it causes a bigger and bigger Self-expansion.

During the lecture we have to pay attention to the harmonic distribution of evidences in time, which similar to the movies, will keep our attention on the lecture.

The function of presentation is to help the communicational process by opening a visual channel above the auditive channel towards the audience. And as we know from the principles of Psychology 2.0, that a good figure is better than 10 pages of written material.

A good speech is based on similar principles. Although different in that it is less visual, far more intellectual tools can be used. The usual set-up is that someone stands on the stage and talks. They may use figures for explanations. The good speech has one or more clear messages for the audience. This message is in most cases delivered as evidence, a new cognitive schema. The greater the distance between the connected matters (for example, if it tries to place something in a political, social, or historical context, which is not obviously expected) the greater the Self-Expansion effect of the creation of the new scheme.

There are different techniques to build up a speech. You can start with the speech's general message, and later explain how did you get to that conclusion. An other widespread method used by speakers is to repeat the path by which he reached the new evidence. This is similar why the Passion of Christ (the last hours of Jesus before he was crucified) is repeated by Christians each year at Easter. The advantage of this method is that many sub-problems, and the pleasure of solving them, can be communicated. (Supposing that this does not happen in order to increase the ego of the speaker by listing how clever he or she was in dealing with these problems.) If the sub-problems are interesting as such, and if they mobilize the cognitive schemata surrounding the cognitive schema to be introduced, it may have a greater effect. This solution makes it possible for those cognitive schemata to connect faster with the new evidence – the new cognitive schema – as they trigger the schemata around the future scheme, so causing increasing Self-Expansion.

During a speech we have to pay attention to the harmonic distribution of evidence over time, similar to watching a film, so retaining our attention.

The function of presentation is to help the communicational process by opening a visual channel above the auditory channel to the audience. As we know from the principles of Psychology 2.0, a good figure or diagram helps more the understanding than 10 pages of written material.

If we talk about the advantages of the visual communication, let us examine what can we say about good figures with the help of the MPP.

The criteria of good figures are widely known:

- it's easy to overview it. It displays only one or two thoughts. In other words we can say that it is focused

- it's clear. Even the most striking illustration is worthless if we cannot identify the parts of it (though it can also be a technique of the lecturer to show too much information if he doesn’t want to reveal the point of the lecture too early and plans to return to an illustration later on).

- and it has to be simple. Congestion (too high information density) frightens us away from trying to understand a picture.

Easy distinctness can be reached by considering that any new cognitive schema can be built only on already existing ones. So the more already existing and widely used cognitive schemata we build on, the better basis of the new cognitive schema we have. So, if we want the audience to understand our illustration we have to apply as less abstract concepts as possible. We can not count on the freshly understood concepts even, as they haven’t subsided yet (=the new cognitive schema has not made the connections with the surrounding ones and had not integrated yet in the audience's knowledge). This leads to the fact that regardless of how it would fasten the process (building a new higher level scheme based on the existing ones), it is not advised to use newly built schemata, unless there is a possibility to re-read it (from hand-out, publication, notes etc.).

Using color codes is beneficial, especially if it fits the general notation (e.g. red = not allowed, green = allowed; just like with traffic lights). In colors we can rely on the usage of Self-expanded colors (vivid, warm colors) to be used for marking positive things, the Self-narrowed colors (dark, cold colors) to use for details indicating danger (e.g. illnesses, viruses etc..)

If we talk about the advantages of visual communication, let us examine with the help of the FIPP what can be said about good diagrams.

The criteria for good diagrams are widely known:

- it is easy to overview it. It should display only one or two thoughts. In other words we can say that it is focussed

- it is clear. Even the most striking illustration is worthless if we cannot identify the parts of it. (Although it can also be a technique of the lecturer to show too much information if he doesn’t want to reveal the point of the lecture too early and plans to return to an illustration later)

- and it has to be simple. Congestion (too high information density) intimidates us in attempting to understand a diagram.

Distinctiveness can be achieved by considering that any new cognitive schema can be built only on those already extant. So, the greater the number of existing and widely-used cognitive schemata we build on, the better the basis for the new cognitive schema. If we want the audience to understand our illustration, we should apply to it as few abstract concepts as possible. We can not count on newly understood concepts, as they have not yet subsided (the new cognitive schema has not made connections with the surrounding ones and so has not yet integrated with the audience's knowledge). Thus, regardless of how it would accelerate the process of building a new higher-level schema based on those existing, it is not advisable to use the newly built schema unless there is the possibility to re-read it, from a publication, notes &c.

Using colour coding is beneficial, especially if it fits the general notation (e.g. the traffic light use of red = not allowed, green = allowed). By using colours we can rely on the use of Self-Expanding colours (vivid, warm) to be used for marking positive things, and Self-Narrowing colours (dark, cold) for details indicating danger or negativity e.g. illnesses, viruses &c.

But what is required for that? One must choose the speed and the level of cognitive schemata carefully. By speed I mean that the Self-narrowing phase has to be well-designed and balanced: if it is too slow (too gently sloaping) it is boring, if it is too fast (too steep) most of the audience will not be able to follow it (they will give up).

So, careful selection of the right level of cognitive schemata is needed in order to ensure that the lecturer can use (can build on the) well-known, shaped concepts (cognitive schemata) that are familiar in the audience. For this the lecturer has to understand what the audience do and do not know. This requires a one-sender/many-receiver type of empathy. The lecturer can collect information on the speed and on whether he did choose the right level from the audience: this feed-back information can have different forms from buzzing, rustling, chatting…to being rapt or completely silent. Or they are listening wide-eyed (the phenomena of being wide-eyed is pupil dilation, a side-effect of Self-expanding).

But what is required for that? One must choose the speed and the level of cognitive schemata carefully. By speed I mean that the Self-narrowing phase has to be well-designed and balanced: if it is too slow (too gently sloping) it is boring, if it is too fast (too steep) most of the audience will not be able to follow it, and will give up.

So, careful selection of the correct level of cognitive schemata is needed to ensure that the lecturer can use, can build on, the well-known, shaped concepts (cognitive schemata) familiar to the audience. For this the lecturer has to understand the limitations of the audience’s knowledge. This requires a one-sender/many-receiver type of empathy. The lecturer can collect information on both the speed and on whether he has chosen right level by using the feed-back coming from the audience. This feed-back information can have different forms, from buzzing, rustling, chatting through to being rapt or completely silent. Or they are listening wide-eyed (the phenomena of being wide-eyed is pupil dilation, a side-effect of Self-Expanding).

(:title Art and the communication of Cognitive Schemata:)

(:title Arts and the communication of Cognitive Schemata:)

Therefore, with our knowledge of the Bible, a common or garden communicational coding/decoding system, we complete the story, understand the picture, and so the new cognitive schema emerges. Those ones who do not know the Bible or differ in their thoughts about the appearance of the first man e.g. the first monkey who could light a fire, or the jackal coupling with the sun and then giving birth to humans instead of her own kind, will not understand the picture. Previously there was a common coding/decoding system.

Therefore, with our knowledge of the Bible, (that functions as a common communicational coding/decoding system), we complete the story, understand the picture, and so the new cognitive schema emerges. Those ones who do not know the Bible or differ in their thoughts about the appearance of the first man (e.g. the first monkey who could light a fire, or the kids of the jackal and the sun), will not understand the picture.

Whenever we talk about Self-Expansion we emphasise that is due to a NEW cognitive scheme. After it is known for people it starts to be boring. That gives the rythm of fashion:

- new things appear (e.g. wearing T-shirts without arms) with a newly born cognitive scheme behind it

- based on the new cognitive scheme new, but lower level schemata are created via deduction (e.g. in the beginning everybody thought that black T-shirts are funny, than somebody tried out the same arm-less T-shirts but in colors)

- when the new cognitive schemata are becoming known by the majority of the population and there are no possibilities for further deduction the clothes or behaviour based on this cognitive scheme disappears and a new one appears and starts to spread (e.g. T-shirts with turtle-neck)

Whenever we talk about Self-Expanding we emphasize that this is due to a NEW cognitive schema. After this new schema becomes well-known it may begin to bore.

When we talk about spreading new schemata we can also talk about fashion. This rhythmical change of new and boring state provides the following rhythm of fashion:

- new things appear (e.g. wearing T-shirts without arms) with a newly-created cognitive schema behind it

- based on the new cognitive schema new, but lower level, schemata are created via deduction (e.g. in the beginning everybody thought that armless T-shirts in black were funny, then somebody tried armless T-shirts in colours)

- when the new cognitive schemata have become known by the majority of the population, and there are then no possibilities for further deduction, the clothes or behaviour based on this cognitive schema disappear and a new one appears and starts to spread (e.g. perhaps armless T-shirts with turtle-necks)

We know that there are good and bad teachers. Moreover, we realize that a teacher we like may be disliked by others, so that there is no absolute good teacher. But how can we conceptualize a good teacher from a psychological point of view?

To discuss this topic, let us ignore the teacher’s personality, and that people prefer others who are similar to them or, in certain instances, diametrically different to them (Newcomb(1961): The aquaintance process. New York, Plt). The examination of the qualities of a good teacher or lecturer may lead us more effectively .

Since we already have a psychological concept of what people perceive as a good feeling in general (the Self-Expanding), we can simply say that the good teacher is a person who elicits a lot of Self-expanding in the audience.

But how can a teacher cause – or create – Self-expanding? He starts by narrowing our Self through presenting the problem (our Environment becomes the problem), the weight or importance of the problem (the Environment gets bigger and bigger), and by then taking us on a journey requiring attention and intellectual effort. He then shows us the path to the solution, and we – individually – shape our new cognitive schema that he wanted to teach us.

An alternative to showing us the path he can drive us so, that suddenly (similar to when driving on a road and after a curve we just face the sea filling in our perspective) we understand the solution in an instance and have an aha experience. The latter one can be called “dynamic lecture” style: the subject appears to become increasingly complex and then suddenly everything falls into place as the new cognitive scheme emerges. Everything we saw before now makes sense. Moreover, we can reach conclusions by ourselves, when we realize a general connection that can be applied both to the present problem under examination and to many similar problems. The ne plus ultra of a good lecture is that when a high-level cognitive schema emerges which has a general influence on our world view also.

We know that there are good and bad teachers. Moreover, we realize that a teacher we like may be disliked by others, so that there is no absolute good teacher. How can we conceptualize a good teacher from a psychological point of view?

To discuss this topic, let us ignore a teacher’s personality, and that people prefer others who are similar to them or, in certain instances, diametrically different to them (Newcomb(1961): The aquaintance process. New York, Plt). The examination of the qualities of a good teacher or lecturer are more effective indicators.

As we already have a psychological concept of what people perceive as a good feeling in general – the Self-Expanding – we can simply say that a good teacher is a person who elicits a Self-Expanding in the audience.

But how can a teacher cause – or create – Self-Expanding? He starts by narrowing our Self through presenting the problem (our Environment becomes the problem) and the weight or importance of the problem (the Environment increases in size). He or she then takes us on a journey requiring attention and intellectual effort, showing us the path to the solution. Individually, we shape the new cognitive schema that he or she wanted to teach us.

An alternative to showing us the path is to drive us, so that suddenly, as when driving on a road we round a curve and our whole perspective is filled with the sea. We understand the solution in an instant, and have an aha experience. This alternative method can be called the “dynamic lecture” style: the subject appears to become increasingly complex and then suddenly everything falls into place as the new cognitive schema emerges. Everything we saw before now makes sense. Moreover, we can reach conclusions by ourselves, when we realize a general connection that can be applied both to the present problem under examination and to similar problems. The ne plus ultra of a good lecture is when a high-level cognitive schema emerges which has a general influence on our world view.

- induction is a characteristic more of a genius than deduction

- painters usually think in images rather than in logical exclusion

Thus, the form of the process is irrelevant, but one thing is certain: a new cognitive schema was established. Regarding our model, as the new scheme emerged, Michelangelo felt the urge to communicate. He was motivated to share his new cognitive scheme with others, which gave him the energy to physically create the picture.

In the process of physical creation technical abilities (knowing how to paint and how to put your internal pictures on a canvas) connect with the quality of communication. So if he would have painted less chiselled, the message had gone through less smooth (the observers would have face more difficulties to understand the message of the painting. ((Luckily in this particular case we face a painting where not only the concept but also the realisation is outstanding. Just please remark on brilliant solution in the structure of the picture: the hand of God barely touches Adam, so accentuating the tension.)

An artist can excel in two ways:

- they can communicate their cognitive schemata intensely; these are the people who we call virtuosi, craftsmen or simply professionals. These people we admire how well they can touch the substance of something (compare with Picasso's apple or a good photo)

- they have such unique thoughts and cognitive schemata about life as such, which we mere mortals rarely achieve. Sometimes these results are consequences of the artist’s different thinking methods: musician think in melodies, poets in words, painters in pictures etc. So they can add us something that makes our life more understandable (e.g. Ingmar Bergman films)

The reception of an artwork is the process of incorporating the new cognitive schema. In doing so, we – the receivers – establish the same connections and thus the same cognitive schema, and then connect that to our existing cognitive schemata. Essentially, the received cognitive scheme becomes part of our thinking, a part of our Self. It also has to be remarked, that the perception is not a unidirectional process. In order to find the proper place of this new scheme we have to consider the right schemas around this future scheme of us. And this is what we call cultural embedding: the schemas around have to be similar to those of the artist. Otherwise the whole process leads to miscommunication.

- induction is more a characteristic of genius than is deduction

- painters usually think in images rather than within logical exclusion

Whatever type of thinking he used one thing is certain: a new cognitive schema was established. Regarding our model, as the new scheme emerged, Michelangelo felt the urge to communicate. He was motivated to share his new cognitive schema with others, which gave him the energy to physically create the picture.

In the process of artistic creation (=physical realisation), technical ability (knowing how to paint and how to convey your internal pictures onto a canvas) connect with the quality of communication. So, if he had not thought so much about it, the message obtained by observers would leave them with difficulties in interpreting and understanding the painting. Fortunately, in this instance we have a painting where not only the concept, but also its realisation, is exceptional. Note in particular the solution in the structure of the picture: the hand of God barely touches Adam, so accentuating the tension.

Artists can excel in two ways:

- they can communicate their cognitive schemata intensely; these are the people who we call virtuosi, craftsmen or, simply, professionals. We admire how well these people can touch the substance of something; compare Picasso's apple with a good photograph

- they have unique thoughts and cognitive schemata about life which is rarely achieved by others. Sometimes, results are a consequence of the artist’s different thought processes: musician think in melodies, poets in words, painters in pictures, and so forth. They can add something that makes our life more understandable, as Ingmar Bergman does in his films

The reaction to an artwork is the process of incorporating the new cognitive schema. In doing so, we (the receivers) establish the same connections and thus the same cognitive schema, and then connect that to our existing cognitive schemata. Essentially, the received cognitive schema becomes part of our thinking, a part of our Self. It also must be noted that the perception is not a unidirectional process. In order to find the proper place of this new schema, we have to consider the schemata around this future schema of ours. This is what we call cultural embedding: the surrounding schemata should be similar to those of the artist. Otherwise the whole process leads to miscommunication.

The point of all art is that a cognitive schema originally created/held by someone – usually the artist – is depicted in either oral or object form which, through its communication, elicits a Self-expanded state in the mind of somebody else by establishing a new cognitive schema. This capability of the artistic works to generate Self-expansion explains why something without any practical use existed always since the men lives on our planet (compare with the very early artworks: cave drawings, fertility sculptures etc.). An additional reason why art always existed is that gave the possibility to someone to spread also those newly born cognitive schemata that ordinary word are not able to be used as communication channel/tool (compare with the situation when you discovered a new and very useful visual form -- e.g. the form of a hammer -- and you have to explain it to everybody in words as arts and sculpture would not exist. If arts would not exists before the tension within you to communicate would create it :) )

The point of all art is that a cognitive schema originally created or held by someone – usually the artist – is depicted in either oral or object form which, through its communication, elicits a Self-expanded state in the mind of somebody else by establishing a new cognitive schema. This capability of the artistic work to generate Self-expansion explains why something, apparently without practical use, has existed on Earth since the first men: the earliest art seen in cave drawings, fertility sculptures &c. In addition, the first artworks provided the possibility to spread those newly-born cognitive schemata that verbal communication was not able to.

According to the Bible the first man was created by God shaping the human body from dust and then breathing a soul into his nostrils, which is the divine difference distinguishing objects from the living. By this process the dust body became alive, and the first man, Adam, was born.

To this point it is a story known by almost everybody. If you would have been there as an outsider and you could have recorded it on a camera, but you would have been allowed to show only one frame of that film, which one had you chosen?

From my side, I would choose as the most important moment when something lifeless becomes alive.

Perhaps Michelangelo was the first artist to realize that if he compressed that universal event (on how we human beings were created) into a single image, he contrasted markedly the divine (the live) with mere matter, the lifeless. Breathing, namely breathing soul into the body, cannot be rendered accurately in a still image, so Michelangelo chose another solution. Artistic freedom enables the visualization of a cognitive schema without the elements required of such a schema. Michelangelo portrayed God breathing life into Adam by touching, a far more concise sign.

However, where is the communication in this process? In Michelangelo’s mind, two new cognitive schemata emerged to provide an outstanding intellectual solution:

- the possibility of depicting the contrast between alive and lifeless by a single image of creation

- in connection with that depiction, the priority of touch before breathing.

The following cognitive schemata required to be communicated are united in one image by the artist:

- the difference between lifeless and alive

- God’s power to provide life

- the state in which we did not exist, and that in which we do

- the visualization of the process of creation

Supposedly, the image itself – as a cognitive schema – came to Michelangelo by an inductive process as he was meditating on creation, about lifeless and live matter etc. But it is possible that Michelangelo came to this image through calculation, design, trial-and-error process or deduction.

I would bet on the earlier, because:

According to the Bible, the first man was created by God shaping the human body from dust and then breathing a soul into his nostrils, which is the divine difference distinguishing objects from the living. By this process the dust body became alive, and the first man, Adam, was born.

To this point it is a story known by almost everybody. If you had been there as an outsider and you could have recorded it on camera, but allowed to show only one frame of that film, which would you choose?

I would choose the moment when something lifeless becomes alive as the most important.

Perhaps Michelangelo was the first artist to realize that if he compressed that universal event – on how human beings were created – into a single image, he would contrast markedly the divine, the live, with mere matter, the lifeless. Breathing, here breathing soul into the body, cannot be rendered accurately in a still image, so Michelangelo sought a solution. Artistic freedom enables the visualization of a cognitive schema without the elements required of such a schema. So Michelangelo portrayed God breathing life into Adam by touching, a far more concise sign.

However, where is the communication in this process? In Michelangelo’s mind, two new cognitive schemata emerged to provide an intellectual solution:

- the possibility of depicting the contrast between alive and lifeless by a single image of creation; and

- in connection with that depiction, the priority of touch before breathing.

The following cognitive schemata required to be communicated are united in one image by the artist:

- the difference between lifeless and alive

- God’s power to provide life

- the state in which we did not exist, and that in which we do

- the visualization of the process of creation

Supposedly, the image itself – as a cognitive schema – came to Michelangelo by an inductive process as he was meditating on creation, about lifeless and live matter &c. But it is possible that Michelangelo came to this image through calculation, design, a process of trial-and-error or by deduction.

I believe that it was by induction, as:

The key issue is not to examine the intensity of a parameter, but to observe the distance between the cognitive schemata of the artist and the observer. For example, in the case of a photograph of an apple, the photographer who sees the apple illustrates it the way we see it in two dimensions. In this case, we do not have to work too hard to understand the uniformity of the two schemata, as the distance is practically zero. However, if we look at an apple drawn or painted by Picasso, we need to make a serious intellectual effort to 'see' the apple, or to ‘see’ the apple the way Picasso saw it. Those who give up before seeing the apple loathe, or at least dislike, Picasso, saying that he only scribbles. They appear to give up before a new cognitive schema has been created. Catharsis did not happen and they did not achieve a Self-expanded state. In contrast, retaining their Self-narrowing causes them to become angry. If they do not understand the picture, they would remain neutral about it.

The key issue is not to examine the intensity of a parameter, but to observe the distance between the cognitive schemata of the artist and the observer. For example, in the case of a photograph of an apple, the photographer who sees the apple illustrates it the way we see it in two dimensions. In this case, we do not have to work too hard to understand the uniformity of the two schemata, as the distance is practically zero. However, if we look at an apple drawn or painted by Picasso, we need to make a serious intellectual effort to 'see' the apple, or to ‘see’ the apple the way Picasso saw it. Those who give up before seeing the apple loathe, or at least dislike, Picasso, saying that he only scribbles. They appear to give up before a new cognitive schema has been created. Catharsis did not happen and they did not achieve a Self-Expanded state. In contrast, retaining their Self-narrowing causes them to become angry. If they do not understand the picture, they would remain neutral about it.

What happens to cultural embedding?

Cognitive schemata themselves are culturally embedded. So, to make a “correct” conclusion on an artist’s cognitive schemata – understanding the artist’s message – requires knowledge of the impulses and information that affected them. For this we need to know the age and culture in which the artist worked, or works. For example, to understand a Renaissance painting one should have a certain knowledge of the Bible, and the visual tools that Bible stories provide. This may communicate a message pertinent to the present, so providing us with a useful cognitive schema in our 21st century life. In addition, establishing these cognitive schemata causes self-expanding.

Comparing Berlyne's model – which somewhat charmingly ignores the question of the cultural embedding – with MPP, we see that MPP can explain not only classic visual arts but also any kind of works of art. For example, it explains the fun of tasting wine, when after some trials we can recognize the taste of spices and fruits within it. Or in reading a poem, when the unstructured cognitive schemata of the poet enter the reader’s mind and establish new connections and schemata. Or in admiring a building, which connects the scheme of the building to value or values it suggests so establishing a new one; for example, the Eiffel Tower as a flexible, elegant, light but ambitious structure representing the French spirit.

Understanding the difference between kitsch and art and between high arts and vulgar arts

Using MPP as a generalised Berlyne-model we can understand the difference between kitsch and art. The main question everybody faces when meeting higher arts is that higher arts are difficult to understand. But in contrary to kitsch or vulgar arts that do not need any intellectual effort to perceive them we realise that our efforts have their profit. We can see that solving the mystery in an artwork (e.g. where is the apple in the scribble) is not a l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake) effort, but enriches us by establishing new cognitive schemata. If we see a half-eaten apple after viewing Picasso’s apple, we might have new associations with it. In case of kitsch we do not have to make any serious efforts but we also do not create cognitive schemata that can be used otherwise than that specific situation when we met the kitsch artwork. And that is why kitsch is neither enriching our knowledge nor our personality.

But we should not forget that vulgar art can also create new cognitive schemata. The difference between the vulgar and high art lies in on what level the new cognitive schemata have born. In the case of a pun the new scheme is born on a very basic level (usable almost in the context where it was created), in a Bergman film, we might establish new cognitive schemata in connection with our whole life (=highest level cognitive schemata).

Identifying these differences between levels of our human life raises a question: On what level do different types of arts elicit their effect?different type of art on what level do elicit their effects? For example, pornography is said to gratify one’s basic instincts. The same is said of horror. Detective stories are said to be of interest because of their excitement. These artistic forms become more and more popular, because they satisfy specific demands. But how do they satisfy these demands?

To date, most of our knowledge is a hypothesis on a particular genre satisfying particular demands. This has resulted in a process whereby we classify genres considering the general human or ethical value (sex, eating, physical needs on the lowest levels; altruism, social work, self-realisation on the highest level -- compare with Maslow-pyramid) of the demand they satisfy. For example, pornography and horror can be on the lowest level, then come the detective stories, and so on up to the high arts. But even critics admit that true genius can place superior messages – those which are of more use in one’s life than simple, targeted messages – in some of the genres classified as inferior; compare with, Edgar Alan Poe's detective stories.

But do these lower level artwork cause an effect just by simply satisfying inferior desires? Even highly reputed people might sometimes listen to rave music, read comics, watch cartoons. In the upcoming paragraphs we try to find out the mechanism behind the effect of different artworks.

What happens to cultural embedding?

Cognitive schemata themselves are culturally embedded. So, to make a “correct” conclusion on an artist’s cognitive schemata – understanding the artist’s message – requires knowledge of the impulses and information that affected them. For this we need to know the age and culture in which the artist worked, or works. For example, to understand a Renaissance painting one should have a certain knowledge of the Bible, and the visual tools that Bible stories provide. This may communicate a message pertinent to the present, so providing us with a useful cognitive schema in our 21st century life. In addition, establishing these cognitive schemata causes Self-Expansion.