< Intimate relationships | List of articles related to FIPP | Confession >

While playing the video press the "HQ" button (in the right bottom corner of the YouTube player) in order to improve playback quality

Fodormik's Integrated Paradigm for Psychology (FIPP)

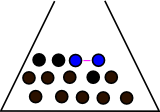

Miklos Fodor developed a model based on three basic concepts (later highlighted in bold) that can describe human behavior in different fields of life e.g. problem solving, love, religion, sex, co-operation. The essence of the model is that it reinterprets the relationship of the Self and Environment, which to date has been considered as a static relationship. Thus, the model distinguishes

Self-narrowing: when the Self perceives the Environment as bigger than itself e.g. in anxiety, fear, making efforts, close attention.

Self-narrowing: when the Self perceives the Environment as bigger than itself e.g. in anxiety, fear, making efforts, close attention.

Self-expanding: when the Self expands into the Environment and perceives it as a part of itself e.g. love, happiness, aha experience, orgasm.

Self-expanding: when the Self expands into the Environment and perceives it as a part of itself e.g. love, happiness, aha experience, orgasm.

The change of the two states can be described with a general pattern, in which the turning point is the emergence of new cognitive schemata, being mental constructions organized on different levels, representing the outside world e.g. concepts, theories, shapes, categories.

The emergence of a new cognitive schema results in a need to communicate, which prompts the Self to associate the new schema with others. The Self-expanding is complete only when such communication occurs.

Example: Problem solving

- Self-narrowing: as we learn more about a problem, finding a solution to it seems to be increasingly hopeless.

- Self-expanding: when the person is about to give up, a new cognitive schema establishes itself, which in turn provides a solution to the problem.

- Communicational pressure: regardless of obtaining a solution to the problem, the person does not experience complete Self-expanding until he can share it with others.

A detailed description of the model and of the basic concepts, with further examples, is provided here.

One virtue of this new model is that it integrates our knowledge of human behavior yet does not contradict psychology’s main discoveries. In addition, it harmonizes with statements of world religions and common sense.

On this page... (hide)

- 1. What is function practice?

- 2. Fodormik’s interpretation of the concept of cognitive schema

- 3. The levels of reality (and the levels of modeling). The multiple aspects of reality

- 4. Cognitive schemata and ideas. Categories and their typical examples. The borders of cognitive schemata

- 5. Archetypes

- 6. Spontaneous Self-expansion

- 7. The establishment and growth of cognitive schemata

- 8. Function practice

- 9. The last detour: playing as an autotelic function practice

(The topic of function practice is closely connected with those of Enlightenment and Problem Solving. It would therefore make the following more understandable if those two topics were to be read first.)

1. What is function practice?

If anyone has seen a child dirtying then cleaning a toy fifty times, then dirtying it again, they will know what function practice is. The same practice occurs when a child learns to stand up, then falls down, then stands up again as long as they are able to physically do so or learn how to stay on their feet. I would not limit use of the concept of function practice solely to children: when a 16-18 year old juvenile finally obtains his driving license all he wants is to drive, and every opportunity to get behind a steering wheel will be taken.

If anyone suspects from the foregoing that the phrase “function practice” is the same as practice, they would be close to the truth. This technical term was invented to distinguish the everyday use of the word “practice” with a more general meaning, one based upon the phenomenon that people can be happy with things that, theoretically, are not beneficial in the short term. Moreover, that a seemingly boring thing can be endlessly repeated while enduring a deal of inconvenience, such as a child continually falling down.

To understand this phenomenon more precisely, we must examine what mental processes occur during function practice. Mental processes connect with cognitive schemata, therefore we should initially consider the nature, formation and function of these schemata.

2. Fodormik’s interpretation of the concept of cognitive schema

A cognitive schema is the key to cognitive science (a new science on the boundaries of biology, neurology, psychology and informatics). There are several hundreds of pages of literature on this subject, but let me explain how I understand this concept.

I have previously described in other topics, and briefly in the introduction to FIPP, that a cognitive schema is the basic element of thinking, that it is nothing more than a mental model of a certain aspect of the outside world. So, almost everything that assists thinking can be considered as a cognitive schema: concepts, categories, theories, symbols &c. (We could go further and imagine schemata in connection with movement and feelings, but these are disregarded here.)

To understand the concept of a mental model, let us recall the definition of the term ‘model’: a model is a copy, which always copies the original thing in a simplified way. It seizes only one or two aspects of reality, and disregards other aspects or dimensions. It does all this to provide the brain, through simplification, with a manageable amount of information. The less important, but still essential, information, can predict accurately enough how the modeled entity will behave. So, we could define the reasoning of all models, and therefore the ultimate goal of cognitive schemata, as: to help with, and provide, adaptation, so that the chances of a person surviving in the outside world should increase by properly representing that world. This happens in the case of every lesson learned, even on a somewhat primitive level at S-R (S-R=stimulus-response: the most primitive reflex-like form of learning) reactions. The lack of the S-R reaction or learning would lead to that individual’s death.

If the mouse we place in a labyrinth did not model the labyrinth in his brain – for example, from stubbornness or stupidity, he did not examine what routes and crossovers there were – and so did not learn where the food was, it would eventually starve to death.

3. The levels of reality (and the levels of modeling). The multiple aspects of reality

In order to understand the function of cognitive schemata, let us take a small detour via the relationship between reality and its mental representation.

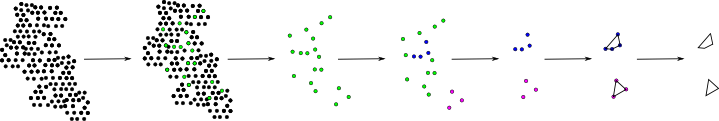

In reality our world is a set of atoms

When talking about reality, in most cases we think of a mechanical image of the world consisting of physically extant atoms, and which obeys the laws of physics. The important thing is not whether the world is like that described above, or whether it includes extra parts which cannot be described with atoms, but that our brain is capable of forming an image of this mass of atoms of only limited complexity. Our brains do not operate on the level of atoms, nor with the representation of atoms, but with relationships. These relationships can be between atoms, but to adapt to our complete reality we must cope with the different levels of their establishment and combinations of atoms. As an example: a person may be affected by 101000 atoms (the number and order of magnitude are illustrative). Of these he might perceive 10100 atoms, equal to 1050 shapes that are combined in 1030 objects, down to one piece of the world in which he lives. Cognitive processes – even if not on an atomic level – will deal with things within the spectrum of the level of (1050 different) shapes to the level of one piece of universe. This presumes that it has to somehow structure these stimuli (the information) and thus the 101000 atoms. Here structuring means extracting the pattern or essence of different groups of atoms by using our mind’s ability to model. As in each person these atoms group themselves differently, it is obvious that our models will also differ, even if we, seemingly, talk about the same things. The difference of our models is reflected in our different reactions to the same inputs.

Decreasing the amount of information

The key to understanding the reason for modeling is that the functioning of our mental abilities is based upon limited mental capacity. We can readily admit that the full complexity of the universe (compared with the number of combinations of the 101000 atoms) is impossible for our minds to grasp. Perhaps it is also conceivable, and parallels our everyday experience, that we can manipulate simultaneously just a few cognitive schemata. We can listen to or concentrate fully on just one source, while keeping several other, different, matters in our heads. (As an example of the limited capacities of our mind, there is a widespread observation in psychology that our short-term memory can store only 5-9 things). Disregarding e.g. 99.5% of the 101000 atoms building our outside world, and purposely not wanting to become known to these, does not seem to be an efficient strategy, as it is possible that we may be endangered by something from that 99.5% territory which we pay no attention to, or avoid. In summary, we can say that we have to live in a world where our life depends on 101000 different things and our brain’s capacity is able to process parallel 101 different things. How can we achieve this?

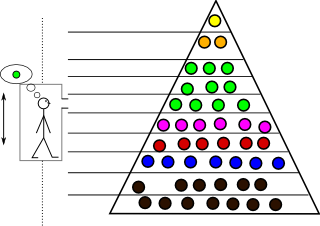

The answer lies in hierarchies. Hierarchies make it possible not just to sum or multiply numbers, but raise to raise them to a higher power. Let us assume that we could raise our capacity by 10% at the cost of a lot of pain, beginning with, say, 10 units. But what is 10, 11 or even 20, compared with 101000? What would happen if we could somehow double or triple our capacity? It is still 20 or 30, almost nothing compared with 101000. However, if we increase the base capacity exponentially, then we can reach ((1010)10)10) = 101000 in just a few ((in our example 3) steps.

What do I mean by modeling based on hierarchy? That the brain extracts the essence: the similarity of elements of a set with different complexity. It does the same on the levels of perception, when creating categories or establishing regularities, and when it forms paradigms. Only the units differ: at the levels of perception the unit is the physical stimuli, in categories it is the properties, in rules it is the experiences, and so on. When the similarities are extracted, these become a new element of a more complex set: firstly, the basic stimuli, then the essence derived from those, followed by the essence of those essences, and so on; eventually, the so-called cognitive schemata, which models a certain detail of our world.

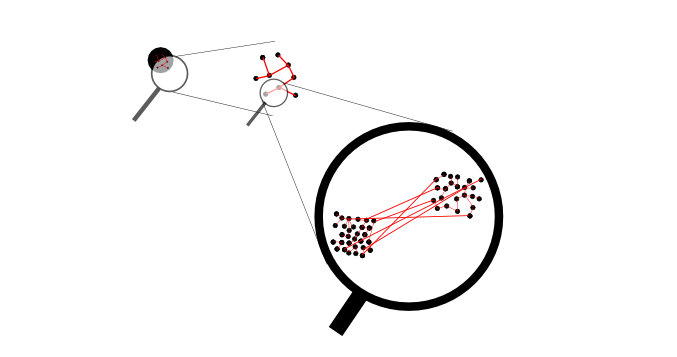

Ability to see different detail levels

This ability is insufficient by itself, as the constant extraction of essence(s) results in less-and-less data-like knowledge of the world; we would see fewer details with which to understand the connections. But to adapt ourselves to our environment, we need access to all information. So as not to lose the full picture, our brain needs to be able to jump, switch between and connect matters between levels (like an elevator, connecting one at a very high level with a basic (lower) one); this occurs because a particular detail may be of interest, next time the overview is important, and so forth. Moreover, sometimes one needs to view the same cognitive schema with its child-schemata. Besides this jumping ability, two additional abilities are required to make this method function: induction and deduction.

Induction and deduction

Induction happens when the brain extracts the essence from lower level schemata. Deduction is when a higher-level schema, accompanied by a lower-level schema that is on the same level as the constituents of the higher one, form a new schema. (Example: I see that 7+7=14=2*7, then I see 7+7+7=21=3*7, and so on until I achieve the number of sevens I want to sum, the result will be that many times 7, the discovery of multiplication. If 50 7s are summed, we will not sum them, simply multiply them: 50*7. In this case, induction took place when we realized that performing many sums and making a multiplication, led to the same result; the lower-level schema was the number 50, the new schema established with deduction is 50*7.)

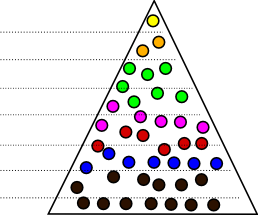

The leveling of the schemata is not uniform

Before we accept that there is a beautiful order in our brains, I should express doubt that we can talk here about a multi-storey construct similar to a pyramid, where every cognitive schema understands which level it is on. I have no proof, only an intuition, that there are also schemata halfway, or one-third of the distance, between stores.

Or suspect that the connections are far more chaotic than in a regular pyramid. Rather, we should imagine the world of schemata as a collection of small and big pyramids that are embedded in each other. Rather than continue this digression, I suggest that we use regular pyramids in the following so that everyone knows where their place is. This will provide a good enough model of our thinking with which to begin.

Before examining cognitive schemata in detail, we should take a further diversion, on the philosophical results of the connections between reality and our minds. That we cannot obtain first-hand information on the physical world due to the boundaries of our perception (e.g. we can not see UV light or atomic particles) is not new. Thus, by considering the above, we can state something of the reality that a person perceives. Unfortunately, nobody can prove that reality is not that you are the only person who exists in the world, and that everything you perceive is only a dream. Or that reading this article is only a dream. (The expanded version of this possibility is explored in the film “The Matrix”, which is based upon William Gibson's books “Burning Chrome” and “Neuromancer”.) If we disregard this possibility, and presume that there are people and other entities around us, then we can also state that the outside world connects with the Self that processes its environment only in the form of those mental representations that process the information. Similarly, our effect on reality can be considered real only in that we give a command to perform an act, then nothing happens, then new information reaches us of the change – presumably as a result of that act – in our representation of the world. (To clarify: there is no proof that anything changes in reality as a result of our intention to perform an action. We simply perceive that we have to change our mental representations in order to comply with the inputs from the world beyond our mind.) Whether anything changed in reality, or what this change might concern, is an insoluble riddle.

Just one more – and final – detour… In my opinion, the concept of the ‘outside world’ is an unfortunate construct: it is so difficult to define objective reality that it seems a pointless exercise. If we accept that reality is not necessarily the way we perceive it, then we immediately start looking on our world from the point of view of a being independent from everybody (e.g. UFOs, God, gods, other transcendent beings &c.). We might succeed as they may exist. And then? It is probable that these independent beings have different organs of sense, different logic, that they model the world in different ways, and may not even think on a neurological basis. However, even if we could contact them – while trying to reduce both their communicational code system and ours to a common denominator – we would inevitably build on our own logic and mental representations to understand what they see. To summarize: we have to accept that the outside world only reaches us through our mental representations. Its cognition is basically determined by our cognitive schemata, which we cannot get rid of, even if we wanted to. Perhaps we achieve the least distorted image of the outside world by recalling childhood experiences, when the majority of our cognitive schemata did not limit the way we saw, heard &c.

Advertisement

This article, and many others, is now available in print.

The book, 'Self-expansion', contains a generalized version of FIPP not available on psy2.org

4. Cognitive schemata and ideas. Categories and their typical examples. The borders of cognitive schemata

Regarding representing the world and categories, perhaps one should recall Plato on ideas. There are many differences and similarities between cognitive schemata and ideas. While a cognitive schema is a mental construction, the concept of ideas refers to the essence of certain things. They are free from mistakes (the perfect circle, the perfect ball etc.) and all earthly things (specifics due to physical appearance).

The two things are not the same. However the reason this requires consideration is that we can consider an idea as the title of a cognitive schema or its theoretical designation. Plato (who invented the concept of ideas) seems to have felt the essence of cognitive schemata when he wrote of generally valid things. However, while he imagined the ideas as something perfect, and the physical objects as poor quality copies of the ideas, in our approach cognitive schemata are more like a list of relations, or a set of rules: an entity which integrates the common property of every object (those that are parts of the category) under discussion. This entity is perfect in that it is a mere mental construction, and reality does not distort it with its own mistakes (similarly with ideas).

However, cognitive schema should not be confused with the typical example of a category, which marks the element of the category that fits the definition of the category best. ((The typical example is a psychology term depicting that element of the set forming the category which is the default example for most people as it has some parameters closely matching the criteria of the category. According to this definition the "typical example" of the category "pet" is the dog or the cat and not the parrot or the turtle, as less people have first-hand experience with the latter animals. This does not make the typical example a perfect fit in the category, as the definition of a category is inevitably simplified. From this point, only matters which fit the parameters of the definition of the category will be the members of the category. While an idea is based upon a convention, as a result of verbal thinking every word has to have the same definition for all people. Nevertheless, one example typifies how this can be interpreted by different people. For example, if I say ‘ball’ to a basketball player, in his head the image of the latest NBA official basketball may appear. If I say ball to a soccer player, he or she may think of the official ball for the latest World Cup.

These parameters/rules/definitions form the essence of each cognitive schema. As definitions of categories they are empty statements, worthless constructs, but when filled with content, new, individual elements emerge (cf. with deduction). Beside these definitions of cognitive schemata another important characteristic of cognitive schemata is their connections with other cognitive schemata. These connections can point upwards (cf. induction), downwards (cf. deduction), or can be on the same level (cf. association). We have not so far examined this last variation.

Association of schemata

Association is that type of connection when cognitive schemata of the same rank connect with each other; the aim of that connection is simply to become a part of a model within a larger system.

Another type of connection is at least as important, namely, those negative connections which guarantee differences. These are the connections that designate the borders of the cognitive schema. They do so by designating a group of cognitive schemata with which it has no common properties; if two cognitive schemata had common properties, they would then be connected positively by these properties. We can also see this principle in real life: we often define something by saying which things are not characteristic of it. This is important in cases when a part of the definition is not the fulfillment of a requirement, but the lack of it. ((For example, when we define animals as living entities that – save for the kangaroo and wallaby – walk on more than two feet; whereas people and birds have two legs, animals can walk on four, six, eight or more legs.

In the next section, we consider in detail how we can imagine these cognitive schemata.

4.1 The road network metaphor

I believe that cognitive schemata are nothing other than connections similar to that of a road network. There are cities (which are akin to cognitive schemata) having districts within in them; this is similar to cognitive schemata forming new units by building them onto each other. There are then the main roads connecting these districts, with one, two or three lanes, which show the strength of the connection between the cognitive schemata. The larger categories of cognitive schemata – according to science – are connected like cities and towns in a country.

Within schemata we find also schemata

The analogy has two important parts:

- the connections between cognitive schemata form a hierarchical network. This means that something is not connected to something else, where the ‘something’ can also be a sub-network. This network and its sub-networks are similar to physics, where particles were divided into smaller and smaller parts, until finally it was realized that there was nothing else, only waves. The difference between particles and cognitive schemata is that in the latter we find nerves instead of waves; and

- the other is leveling: as there is also the street-district-city-country-region-continent series, here we can identify levels as well.

5. Archetypes

As previously examined, the way matters are organized in the world has little or nothing to do with the way we organize the world in our heads, due in part to:

- the limits of the organs of sense (for example, we cannot hear ultrasound);

- the simplification made by the organs of sense in translating the outside world (for example, if we look at a forest we do not see single trees); and

- the limits of our brain capacity and its pre-wired nature and structure

These influence how the world is represented. (For instance, we cannot remember everybody’s name, we see only in 3D, we think in categories, and we build, primarily, hierarchical systems).

The above mentioned limits seem to hinder us in adaptation, as we are not taking our decisions using all available information. This might be true, or these limitations also exist in other human beings, and aid communication between people. That others do not see in the infrared range either, or that others also do not have much greater mental capacity (and so on) enables almost identical models of the world to be made, and so we can share them.

Apart from these limits, people go through the same life phases due to their physical-biological nature: a child is born, has a mother and father, can be either male or female, experiences gravity, acceleration, collision &c. All of these limitations and common points determine the models we build.

Examples of models that are probably attached to the human species, and as such span differences in culture, include:

- growing: the brain has to determine the principal direction or orientation; by following lines of gravity, up and down are perceived. Experience shows that something that is small can also become bigger, by growing. The end-products of growing range between the dwarf and the giant, as definitions of the two extremities. Following this logic, it is no wonder that the concepts of up and down, big and small, dwarf and giants &c. can be found in every culture.

- God: regardless of what people think or believe about the origin of the system they find in the world (the brain gives the system to the outside world, or there is a system in the outside world because a higher power built it as a system) the presence of a system is perceived in one way or another. The operator, the top of the system, is a cardinal point for everyone that we have to name. No matter what we call it - the Creator, a higher intelligence &c. – we are talking more or less about the same thing.

- Extra-terrestrial: if we look at our environment as a system that we live in (we can take the planet Earth or a village in a jungle as our system), there has to be something beyond this system. In this extra-system there might be living creatures. Whether these living creatures are as an African native is to white men, or how a UFO is viewed by a modern man, or witches were viewed in the Middle Ages, it is all the same: we exist in our system, and there is something beyond it. Also, that that something has always been named by ourselves with different names, even if nobody had seen them.

Moreover, we feel fundamentally that these models are not comparable with transient modern constructs, such as say acid rock or the wearing of turtle-neck shirts, but that they carry a certain universality. For Jung, these models had a unique importance, as archaic concepts building bridges to the deepest layers of our psyche. The subconscious (which plays an important rôle in the aetiology of psychic diseases in psychoanalysis) operates using mainly these models, so they form the language of the subconscious. Jung calls them archetypes.

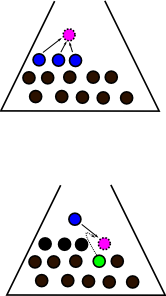

6. Spontaneous Self-expansion

A better understanding of the concept of cognitive schemata makes it possible to be understood more precisely and to explain certain exceptions. Although the FIPP emphasizes the process – of Self-narrowing --> establishing a new schema --> Self-expanding – while ignoring spontaneous Self-expansion. That is, where two schema accidentally merge through a connection and establish something new. The following example is rather tabloid-like, but it sheds light on the process of easy Self-expansion perfectly. Let us assume that somebody’s favorite actress is Angelina Jolie, and his favorite actor is Brad Pitt. He respects both persons and holds them in high esteem, for their beauty and talent. Then he reads that they have married each other. Any happiness he feels about this comes from the establishing of the cognitive schema of a perfect couple on the basis of the cognitive schemata of perfect stars. Of course, there is a testing phase here as well, just as we have seen in the topic of Problem Solving. The person attempts to match the existing information on the actor and actress to determine whether their personalities fit each other and they would form a good couple. Perhaps if Brad Pitt had married Pamela Anderson, that would have established a more contradictory cognitive schema. From this, we can see that it took no serious effort to establish the new schema. Moreover, the fan’s skills and abilities were not questioned while reading the news, so the Environment did not endanger his Self that much. Accordingly, the Self-expansion is not so frenetic either, but is enough to produce the usual sharing constraint, so he might relate this news to other friends and fans in his environment.

7. The establishment and growth of cognitive schemata

The essence and precondition of a cognitive schema are its inner rules which principally define the cognitive schema, whatever they might be: a mathematical formula, a tune or an object. Connecting this rule with other cognitive schemata, the schema becomes increasingly embedded in the net of the pre-existing schemata. In other words, the cognitive schema’s net of connection spreads.

From this description, it follows that there are cognitive schemata with either smaller or greater nets of connections. Those with a smaller net are therefore less determining, and those with greater networks blend with the mass of cognitive schemata. An example of a larger cognitive schemata is of a schema of a man or a woman, which is also connected (either positively or negatively related) with the schemata and other properties (for example, aggression, tenderness, risk taking, compassion &c.) of all the people we know.

The net of connections of cognitive schemata is capable not only of spreading, but also of restructuring and shrinking. They rarely vanish without a trace, since they remain in the form of actual facts. Only their system of connections restructure radically, to the extent that its shape bears no resemblance to the original.

The establishment of a new cognitive schema does not expand the Self solely due to the establishment of the new connections. It is also based on the former experiences that anticipate the number of new connections to be established. For example, when an art dealer buys a Picasso for $1,000, he is neither happy nor unhappy. He has spent a considerable amount of money. But he is almost sure that that expenditure will enable him to sell on the painting and so make a substantial profit for himself; perhaps at the moment of purchase he anticipates how he will spend that profit.

Alternatively, when a new cognitive schema is established, the Self also expands as it expects a number of new connections to be created soon, which pleases it. Perhaps someone discovers a new restaurant in his neighborhood; he is happy that there is a new menu available to try. The cognitive schema of the restaurant will make new cognitive schemata of meals, which connect with the cognitive schemata of taste.

The pleasure of having established new cognitive schema accompanies the testing process previously mentioned, which examines the congruence of the world and the cognitive schema. For example, the restaurant may seem nice, but is it clean? It may be nice and clean, but are the waiters polite, civil? In order to avoid this scrutiny, and so reduce the pleasure of the establishment of the new cognitive schema, in most cases a person will:

- complete any missing information with positive things: the restaurant is nice and clean, so the toilets must also be clean). We do not eradicate our pleasure by inspecting all of the rooms to check their condition;.

- examine the topic at a higher level – by making a so-called “general impression” – before going into the detail step-by-step. For example, if I often frequent Starbucks, I enter one of its outlets anticipating an understanding of its condition that I may never bother to verify. The same applies to the restaurants of a particular district of a city, or in the case of a national cuisine. If I go to a Chinese restaurant, I am more or less aware of what tastes I can expect there.

Advertisement

This article, and many others, is now available in print.

The book, 'Self-expansion', contains a generalized version of FIPP not available on psy2.org

The results of testing increasingly fill and enrich the cognitive schema, resulting in a detailed picture being formed. Naturally, the enrichment of the cognitive schema cannot be reached only with the help of outside stimuli, but it also requires inner processes: we say that we are “ruminating” on a problem. At such times there is no new input, it is only the variables of the structure trying to connect with other, pre-existing and different, cognitive schemata. This happens when someone reads a theory and tries to understand it by bringing up examples, attempting to rebuild it and so on.

Understanding that a cognitive schema has a stable, unambiguous inner structure, and that it is connected – through a few lines – with other cognitive schemata, provides further pleasure. Although the new cognitive schema was established earlier, henceforth it is both usable and ready to make new connections.

Once a cognitive schema is ready for use, it becomes subject to more or less intense verification when in use. Verification is either direct (for example, can we solve something with it?) or meta-reflective (perhaps, can we solve it as quickly as usual?) about the success of its use.

8. Function practice

Please forgive this preliminary – and hopefully not too long – detour, spent on understanding cognitive schemata. We can now attempt to explain the phenomenon of function practice. In the main, it relates to the establishment of cognitive schemata, and the growth of their net(s) of connections. Moreover, we can also say that function practice is no more than all of those attempts to increase the net of connections that are motivated by the reinforcing effect of Self-expansion. The latter is the function pleasure which we can observe in function practice, and which has been previously described in psychology. Function pleasure is the happiness we feel when becoming increasingly successful at an ability we have to learn, or a series of acts as we use them.

However, what is the phenomenon in connection with which we can declare that we are becoming more successful?

As previously seen, after the main connections – the essence of the cognitive schema – congregate, the cognitive schema then begins to shape the system of connections that determine its relationship with other cognitive schemata. In an admittedly artificial manner, we can divide these relationships into:

- inner connections, which organize the constituents of the cognitive schema; and

- outer connections, which organize the relationships of the cognitive schema; and

- other cognitive schemata.

This division is not the best way to view the schemata as these connections do not have to differ in quality merely for occurring within cognitive schemata. Within the cognitive schemata there are also other cognitive schemata; recall that a cognitive schema is established through the integration of other, lower-level, cognitive schemata, or by the extraction of their essence through induction. Perhaps a method of distinguishing inner and outer connections is by measuring the strength or density of those connections. This would be similar to the road network metaphor, showing roads within a city and those leading to other cities. Both inner and outer roads are similar, but while those within the city have just one or two lanes, the roads – or highways – between cities can have three or four lanes.

The greater strength of a connection is due to the inner connections of the cognitive schema having become more harmonic, so making the inner contradictions vanish. The solving of these minor, internal contradictions leads to small Self-expansions. For example, we can hit a ball with a tennis racket, but a good coach can instruct us how we can hit it with more confidence, and with greater accuracy and power. To avoid selecting incorrect methods of achieving these aims we must practice, which makes the connections stronger.

Staying with the road network metaphor, I would illustrate these last two thoughts. That the city is already there (the cognitive schema is established) means that its road system becomes more and more complex – the inner net of connections of the cognitive schema grows – and also has some traffic. What else can then be done to improve what we have, in order to be able to get from one point of the city to another more quickly? (How can we increase the efficiency of the modeling)? To achieve this, we must do away with dead-ends, replace two-way streets with one-way streets (so dissolving mini-contradictions), and by broadening main roads (so strengthening the connections by practice). That is how it looks on the micro level of cognitive schemata.

On the behavioral, macro, level, the previously mentioned function pleasure can be observed: the better we do something, the more we initially like it, but we then become bored with it. The order of this progression is:

- initially, the child or adult cannot solve a problem

- on the basis of “fortune favors the brave”, he proposes a solution

- the solution is often wrong, but the proportion of good solutions begins to increase

- the proportion of good solutions almost completely outnumbers the errors, so the problem can be solved with almost complete certainty

- in dealing with the problem, boredom sets in, and:

- he stops the activity and does not begin again (in the case of a child, shaking a toy; people who retire and who they do not miss their previous job, as they have reached their goal)

- it becomes a necessary, automatic, routine, undertaken by pure reflex (tying a shoelace, multiplying figures)

- the problem is made more complex, testing his success at solving the more complex puzzle (cycling, cycling without hands, on one wheel); operations in different numerical systems, natural numbers, complex numbers, binary numbers &c

On a higher level, this happens in cases of burn-out, when someone becomes bored of a complete profession. (Note that the definition of burn-out varies. Here we do not focus on the aspects of burn-out that is due to over-work, and can be described by as a temporary state of exhaustion. More exactly, we focus on the diminished interest for work and the accompanying depersonalization or cynicism or both, the effect of which are seen in the long-term).

But rather than becoming bored, why do we stop before reaching peak (100%) performance? Why do we not strive to become completely perfect? The answer: after awhile, our investment is so much bigger than the profit or advantage earned that it seems to have become an enterprise which would provide a deficit if further investment were to be made in its development. Even if not a deficit (but from an economic point of view because the alternative cost is the same), a better investment can be made in an enterprise where equal effort promises greater reward. Here, profit and effort should not be thought of as abstract numbers, rather in terms of language of the psyche i.e. Self-expansion and Self-narrowing.

Why is it like that? Repairing small mistakes in an almost complete cognitive schema requires restructuring of the whole schema. However, the increase of performance and competence, which would lead to Self-expansion, is hardly noticeable.

People who become bored of their profession do not realize that they can reach and obtain in other fields of life the Self-expansion they are used to. However, due to a failure-averse attitude, or the lack of a risk-taking attitude, they do not dare to change. They stay in the field where they are acknowledged, they do everything routinely, yet the meaning of their life, and their happiness (series of Self-expansions), is missing.

My comments on function practice could be taken as a mere by-product of human thinking. However, function practice is much more than that: it is the key to understanding thinking and human development. If someone did not want to practice functions, he would not only give up function pleasure, but would stand wholly incompetent in the world. As the establishment, growth and use of cognitive schemata are not to be separated, they take place in a continuum, and the same processes occur. Connections are established the same way, the only question being “Where do we stand, at the base of one or two (when they are established) or 1000-2000 (at the end of function practice). So, although function practice was previously a good concept, if we look at it more closely, we see that it is no more than the normal activity and spreading of a schemata. Being a concept difficult to define, I believe its use should be limited to the one phenomenon, or perhaps two, necessary in children’s psychology.

9. The last detour: playing as an autotelic function practice

Playing is another favorite philosophical question. It has no economic profit, yet it consumes considerable energy and is seemingly undertaken with and followed by great pleasure. Questions arise: why is play established?; how can we define it precisely?; to what can we oppose it (e.g. doing nothing, being bored, working)? Evolutionary biologists have defined play as practicing crucial behaviors (such as hunting and marriage) without any negative repercussions. Psychology describes play as a form of function practice with no specific aim.

Upon this, a key issue remain unanswered: what motivates the play; where does the most important constituent of play – pleasure – come from?

FIPP provides the answer: a great amount of information congregates in a child’s head, which is stored in the form of separate cognitive schemata, the connections between which have yet to be established. (Example: he knows he has grandparents. He has heard about marriage. He knows that his parents are married. When in a tale the grandfather bear meets grandmother bear, he understands that his grandparents are married. Moreover, he realizes that, generally, there is a mother next to a father, and that usually they are married.) So during play, an array of new cognitive schemata are continually being established, which causes frequent Self-expansion during play. We have examined why people like play; the rewards of play are the reason we invest energy in it. Behind the accompanying, and frequent, Self-expansion is that – as the new cognitive schemata are established from existing information, and children lack many basic level connections – children find connections easily. Without realization during play, most cognitive schemata would not be established. We would then have a great deal of encyclopedic – but little usable – knowledge. Another major point is that play is a model of reality which does not contain the inconveniences – in military games, death and injury; in medical games, pain and illness – so the profit is disproportionately large compared with the investment. There are virtually no inconvenient episodes, but the great number of realizations causes a great deal of Self-expansion.

Advertisement

This article, and many others, is now available in print.

The book, 'Self-expansion', contains a generalized version of FIPP not available on psy2.org

This raises the question of why do we not play until the end of our lives? Because play only models the outside world. We manipulate the outside world on a high level in vain; it remains a model. It does not matter if we always win at “Monopoly”, our personal wealth remains the same. If the play-acting is of an exceptional model of reality, it can be a small step to matching it to the real world. This in turn raises the question of personality, principally in connection with our response to stress. As an example, what are our feelings when we begin to play poker with stakes of real money, rather than matches or tokens?

I can state just one difference between play and work: that at work we no longer manipulate the models of mental representations, but the representations themselves, so our actions are irreversible.