- Psychology 2.0

Understanding aggression by using the different types of relationships

< Problem solving | List of articles related to FIPP | Sex >

While playing the video press the "HQ" button (in the right bottom corner of the YouTube player) in order to improve playback quality

Fodormik's Integrated Paradigm for Psychology (FIPP)

Miklos Fodor developed a model based on three basic concepts (later highlighted in bold) that can describe human behavior in different fields of life e.g. problem solving, love, religion, sex, co-operation. The essence of the model is that it reinterprets the relationship of the Self and Environment, which to date has been considered as a static relationship. Thus, the model distinguishes

Self-narrowing: when the Self perceives the Environment as bigger than itself e.g. in anxiety, fear, making efforts, close attention.

Self-narrowing: when the Self perceives the Environment as bigger than itself e.g. in anxiety, fear, making efforts, close attention.

Self-expanding: when the Self expands into the Environment and perceives it as a part of itself e.g. love, happiness, aha experience, orgasm.

Self-expanding: when the Self expands into the Environment and perceives it as a part of itself e.g. love, happiness, aha experience, orgasm.

The change of the two states can be described with a general pattern, in which the turning point is the emergence of new cognitive schemata, being mental constructions organized on different levels, representing the outside world e.g. concepts, theories, shapes, categories.

The emergence of a new cognitive schema results in a need to communicate, which prompts the Self to associate the new schema with others. The Self-expanding is complete only when such communication occurs.

Example: Problem solving

- Self-narrowing: as we learn more about a problem, finding a solution to it seems to be increasingly hopeless.

- Self-expanding: when the person is about to give up, a new cognitive schema establishes itself, which in turn provides a solution to the problem.

- Communicational pressure: regardless of obtaining a solution to the problem, the person does not experience complete Self-expanding until he can share it with others.

A detailed description of the model and of the basic concepts, with further examples, is provided here.

One virtue of this new model is that it integrates our knowledge of human behavior yet does not contradict psychology’s main discoveries. In addition, it harmonizes with statements of world religions and common sense.

On this page... (hide)

- 1. Introduction: the types of relationships between objects

- 2. Perceiving the Environment exclusively by a sole schema that represents it

- 3. The characteristics of separation and compression

- 4. Separation and compression as Self-narrowing effects

- 5. The aggression concept of FIPP and classic psychology

- 6. Aggression and optimal group decision

- 7. The forms of manifestation of aggression

1. Introduction: the types of relationships between objects

Before examining the concept of aggression, let us take a closer look how we define something and which possible relationships two cognitive schemata can have.

1.1 Defining something

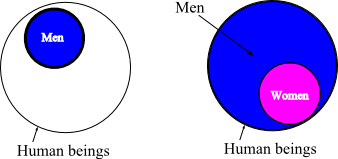

Defining 'Man' in two ways

When we would like to define something (e.g. what is a man) there are two ways to do that:

- in a positive way: we specify what it is (a man is a human being with masculine sexual organs etc.) OR

- in a negative way: we specify what is not (a human being that is not a woman)

Please note three things:

- when we define in positive way, we do not get further information on other things that might belong to the same group (in our case there are no information on women)

- when we define in a negative way, we have to know exactly the definition of those entities that we excluded

- the negative way is not that precise, as there might be other member of the set, that are not taken into consideration (e.g. the hermaphrodites in our case are taken also as men)

1.2 Relationships between two entities

As numbers and logic fundamentally determine both our thinking and our view of the world, the truth of mathematics also affects how we look at – amongst other things – relationships. A simple form of this is to describe the relationship between different entities (e.g. GDP and employment rate; sunny days per year and money spent on ice creams, etc.) as positive (e.g. 3 or 251.92), neutral (nil) or negative (e.g. –2 or –659.34). This describes the implicit way in which two entities affect each other during their relationship. However, until we define and measure the effect precisely – not only its direction – we are satisfied with knowing that

- they help each other’s activity (e.g. when neurons stimulate each other); or

- they hold each other up (e.g. when neurons inhibit each other); and

- the condition in which they have nothing to do with each other, maintains, so the entities are independent.

(According to mathematical logic, helping is addition, holding up is negated addition.)

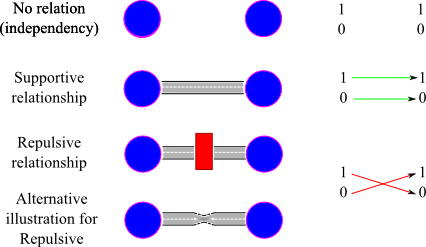

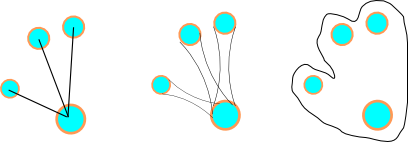

Basic relationship types

Let me define the relationship between cognitive schemata along analogous lines but with a small difference, by dividing the three connections into two differing subtypes:

- where there is a connection between them (as when there is a road between two cities); and

- where there is no connection between them (as when there is no road between two cities).

When there is a connection between them, then:

Supportive relationship (illustration)

- either information streams through it (as when we are free to travel between cities). Let us call this a supportive relationship;

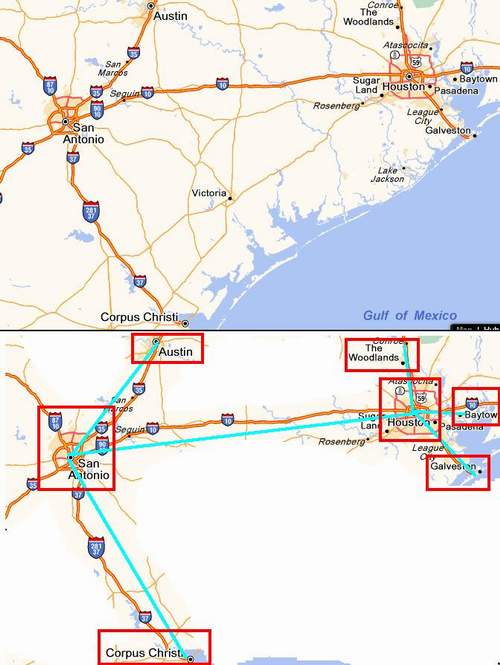

Repulsive relationship (illustration)

- or the streaming of information is forbidden (when in the middle of the road between two cities/countries armed guards make sure nobody passes through e.g. Iron Curtain; Great Wall; The Wall in Berlin). Let us call this a repulsive relationship. A good way of imagining a repulsive relationship is when we try to define something not by what it is, but by what it is not. (For example, we do not say John is a man, rather that John is not a woman).

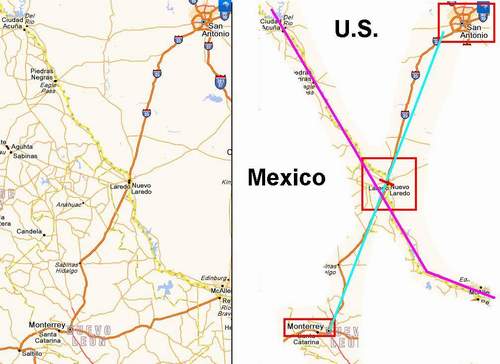

Seesaw (illustration)

To illustrate the repulsive relationship using visual analogy let’s take the seesaw (teeter-totter). The two children sitting on a seesaw are connected to each other, but always in an opposite position. One’s position is fully determining the other’s. With mathematical terms the relationship is A=not(B), that leads that if A changes B has to change as well and vice versa.

What is the consequence of the above defined relationships? In the case of supporting connections, the information streams between the connected schemata so freely, and quickly, that it is virtually impossible from an external viewpoint to distinguish the individual elements from either each other or the whole. On the contrary, repulsive connections actively separate whole schemata from each other, thus limiting what is a part of one and what is not.

Different ways of illustrating a schema and its children schemata

Such divisions of relationships, especially the “merging” effect of supportive connections, explain how it is possible that lower-level schemata and their integrations (the higher-level schemata) are at once different and yet the same.

Why are these connections interesting in the case of aggression? That is what we shall now shed light upon.

2. Perceiving the Environment exclusively by a sole schema that represents it

2.1 The establishment of the absolute ruler schema by integration

As we have seen in the descriptions of FIPP and Function Practice, the relationship of the Environment and the Self is fundamentally determined by how successfully we can represent the surrounding world with models called cognitive schemata. A person dominates his Environment when the schemata used at a particular moment is alone capable of gathering and processing, without contradiction, information in connection with the relevant events, objects and phenomena of the world.

We can define the final goal of all problem solving as the Self representing the Environment with a single unambiguous schema (to have only supportive connections within it). A way of achieving this goal was described in Problem Solving: the mismatched schemata (at least two) represent different parts and aspects of the Environment, out of which a new schema emerges that then represents the former two (or more) schemata in an unambiguous way. The Environment is then modeled as an absolute ruler schema.

2.2 Other methods of establishing the absolute ruler schema

That two (or more) schemata do not match is caused by repulsive connections between them. To dissolve such connections there can be integration with restructuring. In addition, there are two other procedures that lead to a representation in the form of a schema. It is characteristic of both that they reverse the connections which play a rôle in the non-matching, in order to get rid of contradictions. The two solutions are

- separation; and

- compression.

Separation occurs when a supporting connection ends as it connects to a part that makes the schema contradictory. Although gruesome, this is well illustrated in countries where the hands of thieves are cut off as punishment. Another example is where a region of a country separates, declares independence from, its motherland.

In compression, repulsive connections are turned into supporting ones. So, those parts originally separated become connected; for example, when we try to put two non-matching puzzle pieces together by force. However, to add another grisly example, a knife – something which does not fit with a body naturally – is pushed into somebody. Alternatively, where a country is invaded and forcibly subsumed into the territory of the invading country against the will of its residents.

3. The characteristics of separation and compression

Considering the above mentioned examples and descriptions, reversing the connections (making a supporting one out of a repulsive one and vice versa), mostly leads to a socially less valuable output than the initial state. However, separation and compression as such are cognitive processes that of themselves do not have value: they simply improve or weaken the model of their Environment. The common name for the two processes (supporting and repulsive) is aggression. It does not contradict the known psychological fact that there are socially valuable forms of aggression (for example, the military).

That aggression – and within it separation – is a useful process, is easy to observe in the manipulation of schemata. We have seen in Problem Solving that, before establishing a new schema, we must first manipulate the pieces of certain schemata: we attempt systematically to put them together in order to find a new, better fit. The separation of the partial schemata from each other plays a key rôle in this process. Note that, although it would seem logical to attribute the leading rôle to the process of separation, when the new schema is suddenly established from the many parts, it probably does not happen like this. The connections temporarily cease to be (as if there were never any connections) and the completely new schema is formed on the basis of its independence from each other. This also displays to me a difference between the technique of establishing a schema by complete reconstruction, and the technique of dividing them into parts and trying to fit them to each other randomly.

Advertisement

This article, and many others, is now available in print.

The book, 'Self-expansion', contains a generalized version of FIPP not available on psy2.org

Another obvious advantage of separation is seen when the complete schema from which we separate something has no relevance for the Self. For example, when a sculptor crafts a beautiful shape out of a large stone, although the shapeless stone is a schema, it is completely irrelevant for the Self of the person who observes the sculptor. This is the converse of the Self of the sculptor, who has to have a precise picture of where cracks are, where the stone is hard or soft, where and in which direction it can be cleaved in order to shape it. A similar, less artistic example is a quarryman who strikes a stone. The only important thing for him is to make smaller pieces of stone; to divide a bigger whole into smaller parts.

Another example better demonstrates the aggressive nature of separation. If I pull a key out of a lock then push it back, nothing happens. However, if I break and then glue back together a porcelain vase, we realize that the distinction lies in the different cases of separation. For the “key-in-the-lock”, the constituent parts have the schemata that represent themselves; the “key-in-the-lock schema” can integrate them. The pieces of the porcelain vase are not independent schemata, thus the compression (the gluing) is not a possible method of integration. Aggression in this case is akin to breaking the vase into pieces, which cannot be reintegrated (only if we purposefully do it). Separation is exactly the same in both cases. The difference is whether it happens to two separate schemata that are in a repulsive relationship with each other.

Magnets (illustration)

This position can be demonstrated with two magnets, the poles of which are aligned and so should repulse each other. Yet they do not move from each other as outer effects hold them together (two other magnets push them towards each other on the image). As soon as the outer effect ceases, the magnets move to a distance from each other where they no longer repulse each other (according to the law of physics to an infinite distance). The repulsive effect of the magnet parallels the repulsive connection, and the outer cohesive effect parallels the integrative compression.

3.1 Mixed type of connections

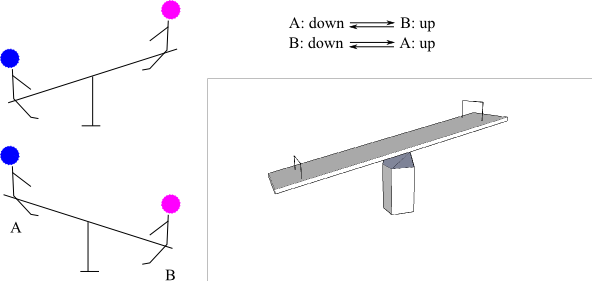

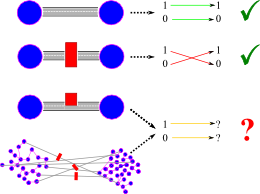

Ambiguous connections lead to uncertainty

The situation is different when not all the connections are repulsive, but there are supporting connections as well as repulsive ones (see the image). In this case, only integration with restructuring can help to avoid mixing of the connections.

The mixing of connections is also of key importance in compression. We can make stable connections, equal in value to connections based on integration, if no repulsive connections remain between the sub-schemata. (For example, when we have a cork and a bottle in our hands we have two separate, distinct schemata. When we begin to cork the bottle, overcoming the friction between the cork and the mouth of the bottle, by overcoming the repulsive effects we establish supporting connections. The supporting connection in this example is the adhesion between the cork and the mouth of the bottle, which does not let the cork come out, even if there is increased pressure in the bottle. We have then established from this corking the “schema of corking”.)

As a summary we can say that mixing supporting and repulsive connections generates an unstable situation due to the uncertainty that it leads to. If a schema is activated an other schema connected ambiguously should activate or not? That is why always the aim is to have either repulsive or supporting relations within two schemata and also their sub-schemata.

3.2 Energetics of connections

We can admit in both separation and compression that establishing and modifying connections take effort. An analogy from chemistry can help in understanding this, that is, the connections between atoms, otherwise known as chemical bonds. Chemistry describes the concept of binding energy – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binding_energy – which is the energy required to disassemble two – or more – connected atoms of a molecule. (Example: in order to disassemble the H2O water molecule to an O and two H atoms, we have to place an electric current through the water via an anode and a cathode. The energy (electricity) is required to dissolve the hydrogen-oxygen connections in the water molecules). To make two atoms join (at least in the beginning) also requires energy (during the joining process the same amount of energy is generated as is needed to dissolve them. Usually this generated energy feeds the process after it has begun: when we light a fire we provide the energy needed for starting, then the process sustains itself). In chemistry, the concept of repulsive atoms is unknown (at least to me). But it is not impossible that we could find examples, similar to that of magnets, on sub-atomic levels.

While on chemistry, we are able to examine the energetics of separation and compression with precise measurements in case of mental processes (as it is difficult to measure) we can, at best, indicate only the types of relations (increasing, decreasing, bigger, smaller) during the processes. It is almost certain that the energetics of the mental processes have nothing to do with the energetics of what is happening in reality. The energy to activate an atomic bomb by pushing a button has no association with the energy released on the explosion. There is also no connection between the physical and mental energy required for the extraction and carving of stone. It seems most likely that it is the number of connections to be changed which most determines the mental energy: the more sub-schemata connected to a sub-schema, the greater the energy required. It is important to note that the one significance of the level of a schema is that a higher-level schema has more sub-schemata, and can thus have more connections; the sub-schemata of lower-level schemata have fewer bonds.

Note: further examination of this bonding energy and the energy flow of a system may provide interesting results if we could ensure that the cognitive schemata operate in accordance with the general systems theory.

Another important question in changing the connections is the relationship of the schemata and the Environment. Mentally, we can only deal with schemata and their related connections. However, the schemata represent the Environment. Until the Environment changes (through our actions or activity or independent of us), there will be discrepancies (contradictions) between what we perceive and the schemata we have. Accordingly, we either modify our schemata so they model the Environment (this is called passive adaptation; an example is how we think about the relationship of the Earth and the stars, whether the Earth goes around them &c.). Or, we modify the Environment to make it accept our schemata (this is so-called active adaptation, as when we excavate passes through mountains to build railways or highways). The third option is to attempt not to realize such differences between the Environment and our schemata (for example, when we do not want to notice that raindrops are falling because we want to barbecue outside). This third alternative is the worst solution. It does not provide a real solution, and eventually the Environment does something which will be difficult to overcome on a cognitive level. For example, it begins to rain so much that it puts out the barbecue fire. Regardless of this, the third solution is widely used, as it often requires less energy than does the real solution.

4. Separation and compression as Self-narrowing effects

The establishment of the schemata means a positive confirmation for the Self (as it has more and more tools to represent the Environment so that it can exert an increasingly greater effect on the outer world, and becomes increasingly safer, and thus has a Self-expansion effect). At the same time, modification of the connections is not Self-narrowing only if a higher-level order can be made by switching the connections. This requires consistent connections (supporting and repulsive at the same time)) between two schemata, or not to have contradictory schemata. For example, trying to avoid the conclusion that: if a>b and b>c then c>a; the first two connections result in a>c, which contradicts c>a.

Inconsistency can be illustrated visually with images in which there are holes in the wall (supporting relationships amongst repulsive ones), or when there are potholes on the road (a few repulsive ones among supportive relationships). Such inconsistencies remaining within a schema do not provide obvious answers if we want to use the schema (for example, superiors command me to simultaneously stop and go; should I stay or should I go?); and it is only a matter of time before the contradictions emerge as problems (e.g. someone likes cats but is also allergic to them. The short-term solution is not to care about it, but eventually the allergy spreads and the person has either to get rid of the cat, or do something about the allergy).

Nevertheless, if we have too many inconsistent schemata it narrows the Self, as with the problem, so we can state that separation and compression cause Self-narrowing. The greater the number and size of the inconsistencies (so that the proportion of the repulsive and supportive connections between two schemata is 50-50, and instead of five or six connections of the schemata connecting with, say, 2000-3000 contradictory connections), the more Self-narrowing is caused.

5. The aggression concept of FIPP and classic psychology

In psychology, there are different groups of aggression according to the aim (e.g. self-defense, territorial acquisition), the method (verbal, physical) and the form (latent, mental, auto-aggression) of aggressive behavior. Despite our feeling that there is something common in these manifestations of aggression, which is why we talk about the same concept – defining it properly and including all the forms of it in the meantime is difficult. The difficulty of the definition arises principally from the duality of behavioral manifestation and mental processes; someone can say something nice about us and yet wish us in hell at the same time, or he gives us his knife as he hopes we will cut ourselves with it. The difference in behavior/mental process is more clearly seen in passive aggression, when we do something by doing nothing. It is the negligence of an altruistic act (e.g. not holding out our arm to prevent somebody about to walk off a pavement into traffic).

5.1 The aggression definition of FIPP

When we first began to understand FIPP, we could admit that Environment is a completely subjective construct. Thus, we could clearly demonstrate both the priority of mental processes and that the change of the Environment is merely a result of the changes of our schemata. Such separation of the outside world and a person’s Self while emphasizing mental functions, explains amongst other things the equality of word, thought, negligence and act preached by different religions. As everything (talking, inaction and movement) is represented on the level of schemata, thus from his psyche’s point of view it is practically all the same whether the child merely has detailed dreams about hitting his younger brother, or actually does so.

In harmony with the above, FIPP defines aggression as follows: aggression is nothing other than the separation and compression performed on the level of cognitive schemata, independent of whether it will appear in any form of change in the outside world.

5.2 Verifying FIPP’s concept of aggression in relation to the results of psychology to date

To verify whether this definition – which appears elegant at first – is in harmony with the current state of psychology, and whether it explains the former connections that have a paradigmatic effect, let us examine some statements of psychology in connection with aggression.

Perhaps the first and most important thought that comes to a psychologist’s mind when he hears the word ‘aggression’ is the frustration-aggression theory. According to this theory, manifestations of aggression are preceded by frustration in the majority of the cases. Accordingly, people respond with either regression (returning to a former stage of personality development) or aggression when they are frustrated. But what is frustration? Psychology defines it as a hindrance in reaching a goal. According to FIPP, this is nothing other than the simultaneous presence of two mismatching schemata (one is the attractive goal, the other the obstacle itself). Rarely do we have the possibility – or time – to integrate the schema of the aim and the schema of the obstacle, so separating the obstacle and the connected aim, then dividing it into parts hoping that with the pieces it will not connect to the schema of the aim. (for example, we break the door, since the wooden pieces of the door cannot prevent us from entering the house). If the disintegrated schema was irrelevant for the Self in the first place (so that it is not connected to anything), then aggression is a solution. Nevertheless – staying with the former example – if we built the door with our own hands and are proud of it, breaking it is not such a good solution.

5.3 The relationship of aggression and Self-narrowing

We have seen from the former descriptions that a problem can have different solutions (solution of a problem: making a new schema out of two non-matching schemata). It can be solved with integration, when there will be one schema out of two schemata, but we can also detach one of them and “terminate” it by slicing it into pieces. The question remains of which one to use.

To answer that we have to understand that Self-narrowing is caused not only by aggression, but also that Self-narrowing leads to aggression. This happens during Self-narrowing and manipulating schemata; series of separations and compressions occur as a pot-luck method of problem solving.

We could say that the strategy chosen depends upon our personality. But we can go further: if we destroy one of the competing schemata, we recognize and record an x amount of Self-narrowing. If we wait until we find the schema (the solution with integration), during the search process we will also have Self-narrowing, the most extreme value of which would be y. The difference between them is that x remains even after solving the problem, while y turns to z Self-expansion where z is in proportionate to y. But we have an amount of uncertainty as we cannot be certain whether our Self-narrowing will turn into the same amount of Self-expansion as a result of finding the integrative solution.

If our former experience shows that (due to our skills) we often find the integrative solution, then we will undergo the y Self-narrowing, because it will be compensated for, and the solution will be stable. If we do not trust our abilities then it is easier for us to live with the x Self-narrowing, and we will choose the disintegrative solution.

According to this, our persistence in trying to find the long-term solution depends on the following:

- the relationship of x and y (which one is larger)

- our experience of how often we find the solution for these kinds of questions (how high is our pyramid of schemata of the field under discussion)

- our ability to bear y Self-narrowing

The relationship of x and y is provided by the situation. Our former experiences and abilities come from self-knowledge; we call it self-confidence. And the last, the ability to bear Self-narrowing, is explained in psychology by the concept of frustration tolerance.

The second point (experience) is determined not only by confidence but also by our tendency to take risks (how risk-averse we are). Other aspects are: the time we have (although finding the solution during the time we have counts in deliberating our chances, and shows a connection with how fast we usually are in finding solutions); and, our general condition (e.g. hormonal condition) which influences the decision as well.

Advertisement

This article, and many others, is now available in print.

The book, 'Self-expansion', contains a generalized version of FIPP not available on psy2.org

At the same time, there are those who have positive experiences with disintegrative solutions, for example, because they are generally in a more Self-narrowed state (they may generally be anxious or aggressive). For them, the x Self-narrowing has a relatively smaller effect, which also passes faster (for example, because their memory is weak). So, more often they will choose another solution than the integrative one (people aggressive in general will tend to use aggressive solutions more often)

According to the foregoing, we can form a more precise picture of which solution we choose compared with simply predicting somebody’s strategy of problem-solving based only on personality characteristics. Also of importance is that the FIPP is both capable of handling the circumstances – the past, the present condition, and the problem, at the same time – and of reducing them to a common denominator.

5.4 The effect of the fluctuation of Self-narrowing on the appearance of aggression

In the previous sub-section, we referred briefly to the rôle of the general condition in the appearance of aggression. Here, we have to consider cases such as when a yogi and an anxious, stressed-out yuppie are stuck in traffic jams. Briefly disregard that they interpret the situation differently, and assume that their position has an equally unpleasant effect upon them. In the momentary Self-narrowing, the yuppie feels increasingly disposed to behave aggressively; for example, he might overtake in the bus lane to reach his aim, for which he gets a penalty for using the bus lane. Compare this with the yogi, whose Self will also narrow, but will not reach the level which would cause aggressive behavior to be exerted. He waits regardless that he will be late.

What happens if the yuppie practices yoga, so that these two people are the same, only that his state of mind differs at two separate times? Their conditions are determined primarily by the events of the previous hours (the Self-expanding and Self-narrowing of those hours), their hormone level and their health. I believe that it is a more efficient strategy if the previously mentioned effects do not vanish in us without trace, but determine their actual level of Self-narrowing as a random number generator. In other words, it is evolutionarily beneficial if the level of Self-narrowing is not constant but constantly fluctuating. Why? Because there are sub-optimal (worse than the optimal but still good) conditions of balance, and to turn away from these conditions we have to modify our general behavior: sometimes we may have to act as a yogi, sometimes as a yuppie. This conclusion is based on the mixed strategy described by game theory, which in most cases achieves a better result than the clean strategies. An example of a clean strategy is if I always answer based on the same strategy (e.g. whenever I become known to a client I raise the question of price; another strategy is to always wait for the client to ask about the price). A mixed strategy is when, by leaving it to chance, we mix two or more clean strategies in certain proportions (so before meeting a client I flip a coin: if it is heads I ask about the price, if it is tails I wait for the client to ask). It is mathematically verifiable that mixed strategies generally lead to better results than clean strategies, even if they are obviously worse in one or two series (e.g. always obtaining heads with the client who does not like if I ask about the price, and vice versa).

From another viewpoint, I would state the following: a fluctuating measure of Self helps in reaching the mixed strategy as a random number generator (as a replacement for flipping coins). Based on all of this, in real life it happens like this: sometimes, quiet people have to make a stand, while vociferous people occasionally have to restrain themselves.

6. Aggression and optimal group decision

The mixed strategy mentioned above also leads to positive results in group decisions as well. Recall Churchill’s famous aphorism: “democracy is the worst form of government except (for) all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”. One interpretation of its meaning is that the opinion of the non-professional masses often pushes into the background those useful opinions that bring good solutions. Often, it is a problem in itself that certain solutions to a problem with multiple outcomes do not even enter the common knowledge or a debate, as they are so much against the mainstream. This happens at the cost of the group’s creativity.

Another example from politics: a state is short of money (a so-called adverse budget), and at first everyone urges increasing taxes which seems logical. This logic is simple and clear to all: the state has money from taxes if the state does not have enough money it needs more if more money is needed the state has to raise taxes. If we do not presume that taxes have an optimal level, then the government will raise taxes endlessly, disregarding the connection that the higher taxes are, the more people try to avoid paying them by sending their money abroad.

So, the governing party urges the raising of taxes. Then somebody appears (the person who impersonates the group’s creativity and who can step out of a certain frame of thinking, an out-of-the-box-thinker) and suggests that taxes be reduced.

In typical cases, others do not listen to him. Moreover, they accuse him of demagogy and populism. However, lower taxes attract more investors from abroad, people begin to invest their money in the country again instead of sending it abroad, and so on. Using this strategy, income from taxes will indeed decrease in the short term, but as trade – and profits (in absolute value) – increase, so more tax income will accrue to the state, even if it is less in pure tax rate percentage terms. Therefore, it is a better bargain for everybody than the government or establishment suggestion.

The same thing happens during the brainstorming of a non-accepting group (for example, a group with autocratic or dictatorial management), where some of the better creative ideas are not aired as the authors of the ideas are afraid of being criticized, so they will not raise them. Fortunately, since the new idea is a cognitive schema the urge to share it – described by FIPP – guarantees that this does not often happen.

These phenomena have been understood for a long time, which is why there is protection of minority opinions. Therefore, to increase the number of available solutions and their diversity, opinions suggested by only a few people will be presented in the decision-making process, but will be derided. Civilized, democratic governments patronize their minorities for similar reasons, as although it is often disconcerting to care about their opinion, a longer-term view shows that their activity expands the repertory of available answers to the demands of world economics and politics.

Let us examine group decisions through an example: a group of ten people reaches a point where they can choose from three directions: left, right, and straight ahead. They have an intuition that the aim is somewhere to the right and forward, but the target is to the left. Say that, at this time, six of them want to go forward, three to the right, leaving one person who wants to go to the left. According to the rules of democracy, they will vote; six win against four, and they go forward. If there is a debate, the ‘forward’ and the ‘right’ will debate, the one who voted for the left will not even have an opportunity to speak unless…

- the group has a system which protects minority opinions; or

- he stops the decision-making process (by any kind of unexpected behavior e.g. crying, shouting &c) and he begins to market his opinion by trying to convince others that he is right.

He may attract attention by speaking louder or being more persistent. This behavior might even be considered aggressive. Moreover, if he does this repeatedly and comes to the wrong result, they will see him as an aggressive person.

However, the real conclusion can be drawn in the opposite way: why are there not Paradisical conditions where nobody is aggressive and everybody agrees on everything? Why do we not just talk, vote, smile and move on? Aggression often increases the group’s creativity by turning our attention to such minority reports, which may potentially lead to the optimal decision. In many cases, emphasized, stubbornly repeated minority reports are disturbing phenomena, and the optimal decisions have to be made, notwithstanding arguments, in a calm manner.

There are two kinds of such aggressive manifestations:

- when somebody becomes aggressive as a random number generator for hormonal or other emotional reasons (a trauma behind one of his memories, or an awful association &c.) and surprises all of their circle. Mostly, this kind of aggression has a “meta-rôle” that comes from being a member of the group (“Hey! Please help me! I’m in trouble”) and serves the goal of finding a new rôle within the group by showing new characteristics and features of the person.

- when a group member obtains important (acquired or constructed) information, and this situation is coupled with commitment to the group. Therefore, the person wants to share the new information at all costs, since if the group makes the idea its own and uses it, the person’s Self will expand as he achieves a better position within the group and will be able to control his companions who function as his social Environment. The simplest example of this is when somebody shouts: “I have found it!” or “I have the solution!” ((“Eureka” is the classic story when Archimedes discovered the elevating force, jumped out of the tub naked and ran around town shouting Eureka=I have found it! This called the attention of others to himself, to share the connection between the weight of the expelled fluid and the weight of the body – a radical discovery then – with more and more people.

7. The forms of manifestation of aggression

7.1 Sharing pro-social and anti-social aggression

As its name implies, the basis of the division is aggression’s relationship with society. In other words, the social benefit – or disbenefit – of aggression. If it is useful, we talk about pro-social aggression, if it is harmful, about anti-social aggression. As soon as we relate to such complex concepts as society, several points of view are immediately raised: what is considered useful by whom (or more precisely by which group of society) and what is not. We can invariably find a group within society which at least understands, and might well support, different forms of aggression. Let us examine it through two examples of aggression, the judgment of which is obvious for the everyday reader:

- Terrorists explode a bomb. The majority will label it as deeply anti-social aggression when innocent people are killed by a group of fanatics. In spite of this, terrorists usually represent the interests of small or large groups (or think they represent them), so we can be sure that the close environment of the terrorists will make them consider it as pro-social aggression. They will see that, rather than innocent people, the dead are representatives of the enemy, and they think this justifies the issue under discussion. They see the whole act as a final possibility, a cry for help from defenseless people who have no tools to fight the numerical superiority other than the tools of intimidation

- Soldiers fight to protect, or create, democracy. Democracy is one of the basic values of western society, so protecting it is a positive act, useful not only for the country that is becoming democratic, but also makes for a better conscience in western societies generally, so it is pro-social aggression. However, residents of a non-democratic country who lived in peace until a foreign country invaded their country, destroyed everything, killed neighbors and friends, will classify it as obviously anti-social aggression. Since they do not know of democracy and its benefits, they have no idea what the soldiers talk about; all they see is devastation.

Before reading the above examples, mention of ‘terrorist’ would bring a negative reaction to mind. Possibly, ‘soldier’ might have obtained a positive reaction. After demonstrating the relativity of these obvious concepts – according to what we consider as social norms – must we still have to reject the pro-social and anti-social division of aggression?

My answer is no. FIPP provides a distinction that makes the division free of values. What we must keep in view to achieve this is that, in most cases, an aggressive act is performed to achieve a goal. This goal is believed to make a positive change in the lives of one or more people; in other words, it helps their Self-expansion. For instance, the terrorist who kills in order to cause Self-expansion in members of the group he represents (cf. people shooting in the air and celebrating after a terrorist act). A soldier kills in the name of democracy to safeguard those at home, and to ensure that the next generation of the foreign country will live a less Self-narrowed life in a democratic atmosphere.

However, the bank-robber who walks into the bank by himself, shoots a cashier and leaves with the money, only cares about his Self-expansion: the moment when he spends the money – obtained at the cost of blood – and provides himself with Self-expansion (in the form of drugs, gambling, expensive sports cars &c.). The situation would be completely different if he shared the money amongst those who need it, as Robin Hood did. Then, although it is ‘blood money’, he would provide many more people with Self-expansion.

One way or another, the person who performs the aggressive act provides himself and his social Environment (people who are important to him) with Self-expansion. However, in parallel with this, Self-narrowing also appears, which he must bear as well. This Self-narrowing has two sources:

- Systems established and controlled by the majority of society (a group of people who have the political power, perhaps the police or judiciary), which serve to preserve the power of the majority in a country; their direct aim is Self-expansion. These include:

- acceptable punishment (he knows that if he gets caught he will be imprisoned for x years)

- the process of criminal investigation (interrogations, observation) and the accompanying anxiety (escaping from the police, limits as to where he can go, who he can meet, which in the end narrows the Self); and

- accusing attitudes and exclusion (nobody is happy when there is a criminal in the company or social circle)

- taking over Self-narrowing of the victims of aggression and their Environment (mourning, loss, inconvenience) through empathy (involuntarily). No matter whether the aggressor wants it or not, the conclusion of his acts will also be represented amongst his schemata, and these conclusions include his aggression’s effect on other people. In addition, the Self-narrowing of the person who suffers the aggression will narrow the Self of the aggressor too.

On reflection, we talk about pro-social aggression when the Self-expansion we obtain with aggression is greater than the Self-narrowing arising from it. On this basis we talk about anti-social aggression when Self-narrowing is greater, and Self-expansion when it is smaller.

As in every concept and relationship in connection with people, we should not underestimate the rôle of subjectivity. Since the Self-expansions and Self-narrowings caused by the act determine the measure of Self-expansion, we have to consider several points of view. If we wish to place the recorded Self-expansions and Self-narrowings in mathematical terms, we can imagine it as the result of the following points:

- how many people are affected negatively (a) and positively (b) by the aggressive act

- how much were the people (c+ and c-) affected individually (by how much and in what direction did their Selves change)

- through what distortions did the changes of the other people’s Selves reach the aggressor (d)

(More precisely: dSelfaggressor=Summ(f(dSelfi) ), where f(x) is the distortion as the Self-change reaches the aggressor, dSelfi is the changes of the Selves of i people – this contains those who profit from the aggression and (with the reversed sign) those who suffer from it.)

By way of illustration of how important these points (a.-d.) can be:

- many people are happy, because a bad person will be punished: a=1; b=many

- many people suffer because of the pleasure of one person: a=many; b=1

- when an evil person who has been chased for a long time is finally caught and punished, people are very happy: a=1; b=many; c+=big, c-=big

- one person’s pleasure is inconvenient for a lot of people: a=many; b=1; c+=big; c-=small

- the environment of a dictator arranges the life of the dictator in a way that he only meets happy people: d=strong distortion

The rôle of subjectivity comes to the fore in determining the precise values, but these values change over time. A dictator who kills many people may see his nation initially happy and grateful, then his nation forgets or turns against him. Although the happiness of the nation may have been genuine, it is now gone. The losses caused by the killings remain constant; murder, aggression, separation are generally lasting as they cause irreversible changes. Thus, it can happen that a celebrated hero can be considered as a common murderer, or he may consider himself a common murderer, and he has to bear considerable Self-narrowing.

7.2 The division of verbal and physical aggression

Previously, the Hungarian police never intervened in family debates unless there was violence: the spouses could shout at each other, they could terrorize each other mentally, but the police attached aggression only to acts of violence (on the grounds of practical consideration). This example may divide physical and verbal aggression in an unhealthy way, as they are similarly represented in the brain. The power of speech can astonish us by its intensely subjective nature of human beings, and by its equality of mental processes and physical reality. Somebody swearing at another person appears to be nothing from a strictly physical point of view. But in sending sound waves in a certain tone to that other person, it can elicit a much greater reaction than if we, say, broke somebody’s arm or leg.

Advertisement

This article, and many others, is now available in print.

The book, 'Self-expansion', contains a generalized version of FIPP not available on psy2.org

Both physical events and verbal communication activate cognitive schemata in our brain, as well as our thoughts and fantasies. That is why, according to the FIPP’s approach, the forms of aggression are reduced to a common denominator; also, why their aggression definitions show no difference. If somebody remains certain of the superiority of the physical world over mental processes, compare what would then hurt him more. What if your partner physically cheated on you once with a faceless and unknown person and she never saw that person again? Or if, although nothing actually happened, but you came to know that your partner dreamed day and night in detail about how good it was to leave the reader for a friend and start a family.

A textbook example of verbal aggression is swearing, which is nothing other than encouragement in calling for the stepping over – or on – of sexual taboos. The rôle of taboo (untouchable, unquestionable things, acts, thoughts; stepping over them is coupled with irrational fear e.g. incest taboo, respecting the dead) is from the very first to serve as an unquestionable axiom and frame of reference within the Self and society, while determining its limits. Their limiting function also means a repulsive connection towards other schemata. Therefore, for example, there is a repulsive connection between a man’s schema, which represents sexuality, and the schema of his mother. Swearing is an attempt to turn it into a supporting connection with the verbal aggression’s compression. Verbal aggression, with its technique of canceling compression of the limits of the Self, endangers the Self itself. For instance, if somebody is called a bastard, then his full identity is questioned. He may begin to doubt the supportive, unsullied image of his family. What may be instilled instead is rootlessness, and the fear of a vacuum in family history. In this example, the power of ‘bastard’ lies in the connection to the family; separation from the mother and father would endanger a central element of everybody’s identity. In addition, being a bastard questions the schema of the father’s person; it questions the whole identity. In addition, identity is a concept which is in close connection with the measure of the Self, so the faltering of identity narrows the Self, which then leads to aggression.